On the slopes of Monte Corvino, where the Lepini Mountains look towards the Agro Pontino, there is an abbey distinguished by beauty and simplicity. Valvisciolo Abbey seems to exist in this place since eternity, but its origins are uncertain and lost in time.

The forgotten origins of Valvisciolo

Lubin, the most ancient and important historian of Valvisciolo Abbey, reports that it was founded by Greek monks, “Illam primitus incoluere Monachi Greci”1. They were probably the Basilian monks of San Nilo, who settled in Latium in the 10th century. However, it is not known whether the monks built an architectural complex or lived in the natural caves of Mount Corvino, since they were anchorites2. Historiographical sources do not suggest neither why they decided to leave Valvisciolo, nor how long they lived there.

The Knights Templar and Valvisciolo Abbey

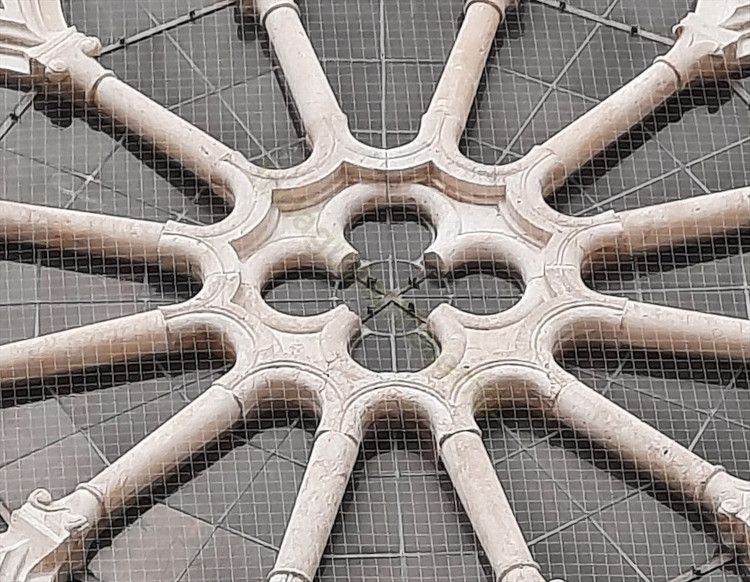

The Abbey belonged to the Knights Templar. This is suggested by a Cross Pattée carved near the central portion of the rose window. Hence, it shows that this Order commissioned at least the renovation of the facade.

The last historian of the Abbey, Cistercian Father Remigio Facecchia, reports that the Basilian monks “abandoned the site of Valvisciolo and never returned. This happened about the first decades of the 12th century, when the Knights Templar arrived”4. Some authors, such as Raymondi5, Pantanelli6, Angeloni7, argue that the Templars constructed a new Abbey, then they could be its founders. A first monastic complex dates back to that time and the church, with a single nave, named after Saint Peter.

The arrival of the Cistercians

The Templars did not stay long in Valvisciolo. Father Facecchia reports that in approximately 1166-1168 Cistercian monks joined the Abbey. These monks came from the nearby monastery of Marmosolio, destroyed by Frederick Barbarossa:

“knowing that they could find an immediate accomodation in the territory of Sermoneta from where the Templars had left, they went there and settled there permanently […] to the existing church, St. Peter’s, they added the name of their destroyed church, St. Stephen; and to the buildings left by the Templars, making the appropriate changes for the construction of a real Abbey, they nostalgically gave the name of their lost Marmosolium”.

Don Remigio Facecchia, La badia di Valvisciolo

Later the cloister was added, which gives access to the refectory, the dormitory and the chapter house.

The historical reasons of the Cistercians’ arrival

In addition, some historical events supports Father Facecchia’s testimony. In the 12th century Italy was divided between the Holy Roman Empire in the North and the Norman Kingdom of Sicily in the South. The Pope’s territories, including Rome, lay between them. For a long period after the Concordat of Worms (1122) the papacy had favoured the Emperor. However, when Adrian IV signed peace with William I of Sicily (Treaty of Benevento, 1156) the relations changed. The Pope and the emperor Frederick Barbarossa entered a phase of conflict.

This situation became more tense with the death of Adrian IV. The conclave convened to elect a successor nominated two popes: the Sienese Rolando Bandinelli, by an overwhelming majority of cardinals, under the name of Alexander III, and the antipope Victor IV. After an initial attempt at conciliation failed, Frederick I publicly supported the election of Victor IV, born Ottaviano dei Crescenzi Ottaviani. Alexander III took refuge in Lazio, near Sermoneta. The consecration (1160) and excommunication of the Emperor took place at Ninfa. Hence, as mentioned by Father Remigio Facecchia, Barbarossa destroyed all the monasteries in the area and the enemy city of Ninfa.

History and monasticism, the Templars guardians of Valvisciolo

Valvisciolo Abbey was not destroyed, probably because Templars were the administrators and they did not explicitly support papacy’s policies. For this reason, the Cistercians of Marmosolio took refuge in Valvisciolo between 1166 and 1168.

The toponym Valvisciolo

The toponym Valvisciolo is certainly of a later period. In the 13th-14th centuries Valvisciolo denoted the Abbey situated in the Valley of the Nightingale (Vallis lusciolae) or of the Cherries (Vallis visciolae) that grew in the Lepini Mountains in the Middle Ages.

Valvisciolo Abbey and the end of the Knights Templar

After the arrival of the Cistercians, the Templars in Valvisciolo did not go away. Father Facecchia affirms that:

“in 1312 the Cistercian community of Marmosolio (nowadays Valvisciolo) rapidly acquired a large number of monks of the same observance from a monastery located in the territory of Carpineto romano”.

Don Remigio Facecchia, La badia di Valvisciolo,

These words recall the history of the Order of the Temple, dissolved in 1312 by Clement V with the bull Vox in excelso. Cistercians were very close to the Templars. Their founder Bernard of Clairvaux had promoted the granting of a rule to the militia templi during the Council of Troyes in 1129. Therefore, after the dissolution of the Order many Templars probably took refuge in Cistercian monasteries, including Sermoneta. Facecchia then reports a curious legend. He narrates that, while the last Master Jacques de Molay was burning at the stake in 1314, the lintels of the Templar churches broke. It is a bizarre coincidence, but a deep crack seems to broke the lintel of Valvisciolo.

Templar architecture and symbolism of Valvisciolo Abbey

Valvisciolo Abbey fully reflects the artistic and stylistic rules of Cistercian architecture. The severe salient facade has a central portal and a magnificent rose window, possibly made by the Knights Templar. The entrance lunette preserves pictorial remains of a Virgin and Child, Saint Stephen and Saint Peter. A concave molding frames the rose window, which through a radius of twelve columns converges to a central cross.

Inside the church, rectangular pillars separate the nave and two aisles of five bays, with no transept. The building is structured according to the geometric figure of the square8, symbol of harmony and perfection of creation. The transverse pointed arches are typical of the Cistercian-Gothic style that characterizes the Abbey. A thin pointed arch divides the chancel into two bays. The nave hosts a clerestory with single-lancet windows. However, the chapel of San Lorenzo, frescoed by Pomarancio (1586-1589), interrupts the spiritual and figurative austerity, according to the Cistercian memento mori philosophy.

A treasure of symbolism: the cloister

The cloister is the most important space inside Valvisciolo Abbey in terms of history, art and symbolism. Located southeast of the church, it consists of four perimeter galleries with cross vaults forming a square.

The cloister gives access to all the other spaces of the monastery. One hundred and twelve twin columns in travertine divide the perimeter galleries with a rhythmic and proportionate repetition of small arches. The recurrence of the number twelve – also in the rose window – is not random. It symbolizes the totality of all things: twelve were the tribes of Israel, the apostles, the doors of the heavenly Jerusalem. The cloister of Valvisciolo is an ideal representation of earthly creation and God’s work.

Cloister capitals of the Valvisciolo Abbey

The sculpted capitals of the columns show a particular mixture between classicism, Cistercian Gothic and typical features of local artists. They all have the same type of Ionic volutes and the waterleaf motif. However, they differ in some decorative elements of important symbolic value, probably associated to the Templar presence in Valvisciolo. Among these, the Flower of Life, figure of resurrection, and the Agnus Dei.

Also, between the volutes of a time-blackened capital is a curious chalice-shaped carving. It evokes the Gospel and the cup of the Last Supper. Christian tradition also identifies the Holy Grail as the chalice used by Joseph of Arimathea to collect the blood of crucified Christ.

The Merels Board

Valvisciolo Abbey and its sacred engravings are an important historical testimony to the link between symbols and their authors, the Knights Templar and the Cistercians who lived there. Near the capital with the Holy Grail is the Merels Board, engraved on the walls supporting the columns. This symbol could represent the ancient Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem. In fact the name of the Pauperes commilitones Christi templique Salomonis, known as Knights Templar, is due to it.

Sacred Center and Solomon’s Knot

The Temple of Solomon was a sacred center of humanity. Templars, who had their headquarters in Jerusalem in the area that had housed the Jewish Sancta Sanctorum, used this concept. It is not by a coincidence the plaster of Valvisciolo cloister hosts the symbolism of the Sacred Center. In fact, after its construction, the construction of some reinforcing walls aimed at better support the weight of the vaults. Thanks to the restorations of the 1950s, some portions of the hidden plaster became visible due to the removal of these additions. The covering layer of the wall ensured the preservation over time of numerous engravings that reveal a very rich symbology.

Moreover, it is possible to observe some Solomon’s Knots – symbol of the inseparable union between God and man – and the engraving of the Sator Square.

The Sator Square of Valvisciolo Abbey

On the eroded plaster it is difficult to read the words SATOR AREPO TENET OPERA ROTAS, composing the famous phrase of the Sator Square. This archaeological mystery is visible in many sites of Europe and Middle East belonging to different periods. Scholars disagree about the meaning of the words, which often form a square of twenty-five palindromic letters, and the symbolic meaning. In this case it is improper the use of the term square, since the Sator of Valvisciolo is circular.

The epigraph has Roman origins, since the oldest was found in the archaeological area of Pompeii. Nonetheless, in the Middle Ages it was reinterpreted with new meanings. It is possible that Christian exegesis considers the translation “the sower, with his plough, holds the wheels with care” as God’s creation. This is why the Sator Square is observable in a mosaic floor of the Collegiate Church of Saint Ursus in Aosta (12th century), in the presbytery mosaic of the church of San Giovanni Decollato in Pieve Terzagni (12th century), on a stone block outside the Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta in Siena (13th century), on a wall around the ruins of Brusaporto castle.

The palindrome phrase was used in the Middle Ages, perhaps by the Knights Templar, with a specific sacred function. It identifies the work of God guiding creation with his Word. The Merkavah, in biblical theology, is the chariot of fire that reaches all the corners of the Earth, figure of the Holy Scripture. We can imagine the somber figure of a Templar who, as the shadows fall at vesper and the torches flicker dancing flames, turns his eyes to heaven and blesses God for the beauty of the creation.

Samuele Corrente Naso

Notes

- In notitia abbatiarum Itali, p. 365 ↩︎

- B. Capone, Vestigia templari in Italia, Edizioni Templari, 1979. ↩︎

- Photo by Pietro Scerrato, CC BY 3.0, image. ↩︎

- Don Remigio Facecchia, La badia di Valvisciolo, Tip. Eredi F. Ferrazza, Latina 1966. ↩︎

- M. Raymondi, La badia di Valvisciolo, Notizie e ricerche con illustrazioni, Stabilimento tipografico Pio Stracca, Velletri, 1905. ↩︎

- Canonico B. De Lazzaro, Memorie storiche sulla Badia di Valvisciolo di Pietro Pantanelli, Velletri, 1863. ↩︎

- Canonico L. Angeloni, Viaggio di Sua Santità Papa Pio IX nella Città e Provincia di Velletri, Tipografia Angelo Sartori, Velletri, 1863. ↩︎

- G. Cristino, L’abbazia di Valvisciolo: un esempio di architettura cistercense fra romanico e gotico. Tracciati, proporzioni e segni, in Il monachesimo cistercense nella Marittima medievale. Storia e arte, Atti del Convegno, Fossanova-Valvisciolo, 24-25 September 1999, edited by R. Castaldi, Casamari, 2002. ↩︎