It is a fascinating journey to trace the “Flower of Life,” a modern term used to refer to the geometric representation of a hexapetal flower that belonged to different eras and civilizations1. Similar depictions were found in Europe, the Middle East and ancient Egypt. It is not always possible to fully reconstruct the meaning of this symbol, especially in the most ancient cultural contexts that saw in it an important complement to rituals and mythical cosmogonies. Its wide dissemination suggests, however, that it was an image of some archetype common to all humanity, connected to concepts of regeneration and new life.

Early evidence in the Bronze Age

In Europe we find the Flower of Life as early as the Mycenaean civilization in the late Bronze Age. The symbol was featured on some gold discs, placed inside the burials in the 16th-century B.C. Circular Tomb A of Mycenae, to propitiate the passage of the dead into the afterlife. Like the flowers of the fields, in fact, the dead were also believed to be reborn to new life from the bare ground. It is no coincidence that on the same supports we find the octopus, an animal capable of regrowing its tentacles, and the spiral, a figuration of the generating force of nature.

At the same time the symbol was in use in northern Iran: artifacts dating back to the 15th century B.C. with the Flower of Life engraved on them were discovered in Marlik2. The findings were part of the grave goods accompanying the deceased from about fifty burials belonging to the local culture.

The Flower of Life and the Ancient Egyptians

A wonderful composition with the Flower of Life was later made on a granite pillar of the Temple of Osiris (Osireion) at Abydos, a building commissioned by Pharaoh Seti I during the 13th century B.C.4 Osiris was for the ancient Egyptians the deity of death and rebirth, a fact that suggests a certain continuity of meaning associated with the symbol across cultures. Myth relates that the god was killed by his brother Seth, then dismembered and thrown into the Nile. But his wife Isis, with the help of Nephthys and the magical arts, brought him back to life, albeit briefly5. Isis, in fact, found the pieces of her husband and reassembled his mummy so that she could have the time to generate with him Horus, a child-god destined to overcome the evil Seth. Therefore, in Egypt Osiris was the lord of the underworld.

The Flower of Life and Iron Age cultures

During the Iron Age the Flower of Life spread throughout Europe and the Middle East through the trade routes that traversed the Mediterranean. The symbol is found on the bottom of an eighth- to seventh-century B.C. cup with mythological scenes from Idalion in Cyprus and housed in the Louvre Museum.

In Assyria, during the last stages of the Empire, the Flower of Life was placed on numerous artifacts now housed in Baghdad Archaeological Museum. Most importantly, however, it was used to decorate the floor of King Ashurbanipal’s palace at Dur Šarrukin, which dates back to 645 B.C.7 It is possible that in Assyria the depiction of the symbol was connected to the worship of Baal, a solar deity of fertility and thus related to the concept of the rebirth of nature.

Among the Etruscans it was represented on an urn at Civitella di Paganico and on the Auvele Felùske Stele of ancient Vetulonia, both from the 7th century B.C. The funerary stele was placed in an upright position and served as a marker for the grave of the deceased. Auvele Felùske, depicted as a proud warrior armed with a double axe and a circular shield, on which the Flower of Life is still in plain view, constituted a wealthy member of his community.

The symbol was commonly used by the Daunians, a population settled during the Iron Age on northern Apulia. Like the Etruscans, they placed it on their own funerary stelae, dated to between the 8th and 6th centuries B.C. and preserved in the National Museum in Manfredonia.

The Celtic flower and the Sun of the Alps

In Northern Italy, popular tradition remembers the flower as the Sun of the Alps. Throughout the Alps it is easy to come across depictions of the symbol dating back centuries, particularly inside houses of worship or on the doorways of private homes in municipalities. Tradition suggests that the origins of the custom should be traced to the Celts, who once settled in the regions of northern Italy. Of this we have no irrefutable archaeological evidence, although it is likely that the Flower of Life was somehow introduced into the art of such peoples, who made extensive use of knotted and woven plant decorations.

In any case, the naming of the Sun of the Alps makes it clear how it retained over time the significance associated with life and fertility, which depended precisely on the sun’s movements throughout the year. The spring equinox, for example, marked the awakening of nature, and first of all, the daffodil, not surprisingly a hexapetal flower very similar to the Flower of Life, bloomed in the Alps.

Instead, we have several indications of its use in other part of Europe subject to Celtic influence. For example, the Cantabrians used to carve it on funerary stelae during the 1st century B.C. In Galicia, archaeologists rediscovered it within the oppidum of Santa Tegra, a settlement that developed in the centuries following the Roman conquest of the region, associated with the so-called Castro culture.

The Flower of Life among the Romans

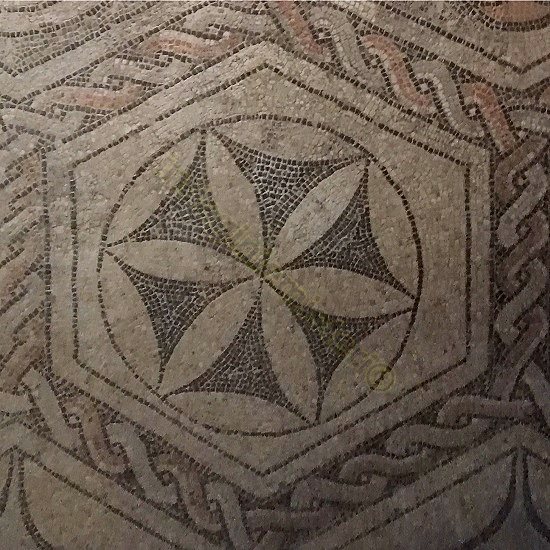

Romans, too, encountered the Flower of Life through the depictions of it by the peoples of the Italic peninsula. The symbol soon became a sought-after decorative motif in the mosaic floors of private homes, especially in the imperial age. Thus we find it in the Domus dell’Ortaglia in Brescia, used between the 1st and 4th centuries A.D. and now included in Santa Giulia’s complex. The frequency of use suggests that, in addition to the purely aesthetic aspect, the symbol had a deeper value, perhaps apotropaic or auspicious. It is possible that the Flower of Life was placed as a guarantee of existence, so that the lives of the inhabitants of the domus might be like the sun that sets each day in the evening and rises again in the morning, or like the daffodil that blooms at the beginning of spring.

Christian reinterpretation of the Flower of Life

With the rise of Christianity in Europe, the Flower of Life could only become a metaphor for Christ, the one who had died and then risen again. Likewise, the symbol continued to be used in cultic or funerary contexts as a foreshadowing of the resurrection that awaits all people at the end of time. We have important evidence of the hexapetal flower in early Christian complexes, such as at the Patriarchal Basilica in Aquileia, and also in the art of the Lombards in Italy. In the church of San Pietro in Gemonio, Lombardy, it was painted on an altar dating, it was assumed, to the Liutprandean age (8th century).

In the Middle Ages the Flower of Life reached the height of its popularity as it was adopted by a number of monastic-chivalric orders, including the Knights Templar. The symbol’s presence is thus observed at the Templar church of San Bevignate in Perugia and in numerous other houses of worship scattered throughout Europe.

The Flower of Life and Leonardo da Vinci

The geometry of the Flower of Life continued to fascinate the world in later ages. Illustrious scientists and literate people saw in the symbol the perfection of form and universal harmony. Among them was the genius of Leonardo da Vinci, who studied its mathematical properties in the Codex Atlanticus, a precious manuscript now preserved in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan.

Leonardo probably sensed in the geometric construction of the Flower of Life a sacred meaning, so much so that he realized it in many pages of his work. The design could be obtained by drawing a circle with a compass, a metaphor for perfection and the totality of things, and six other circumferences intersected with it. Such a procedure seemed to resemble the divine creation, which was completed in exactly seven days and gave birth to the cosmos. Moreover, was not that hexapetal Flower a symbol of rebirth and generation? In it was manifested the relationship between macrocosm and microcosm, its numerical correspondences revealed the secrets of the Universe.

Samuele Corrente Naso

Notes

- D. Melchizedek, The Ancient Secret of the Flower of Life, 1999. ↩︎

- G. N. Kurochkin, Archeological search for the Near Eastern Aryans and the royal cemetery of Marlik in northern Iran, in South Asian Archaeology 1993, ed. A. Parpola and P. Koskikallio, vol. 1, Helsinki, 1994. ↩︎

- Photo: 1985 Photo RMN / Pierre et Maurice Chuzeville ↩︎

- P. J. Brand, The Monuments of Seti I: Epigraphic, Historical and Art Historical Analysis, Brill, 2000. ↩︎

- C. Lombardi, Il Grande Inno ad Osiride della Stele di Amenmose (Louvre C 286): la dea Iside, 2010. ↩︎

- Inventory N3454. ↩︎

- G. Perrot, C. Chipiez, A History of Art in Chaldæa and Assyria, London, 1884. ↩︎

- By Marko Manninen – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, image. ↩︎

- By David Raúl Esteban Redondo – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, image. ↩︎

- By Froaringus – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, image. ↩︎