On the summit of Mount Pirchiriano, like an ancient guardian protecting the valley, stands the marvellous Saint Michael’s Abbey. It is an ancient and admirable place of faith, towering 962 metres above sea level, almost seems to reach towards the sky: it can only be accessed by a steep climb. The ascent is a metaphorical path of mystical spirituality that leads the traveller from the lower Susa Valley to the gates of Paradise.

The origins of the Michaelic cult

The spread of the cult of St. Michael the Archangel in Italy, and contextually in Susa Valley, is due to the Longobards. When, in fact, Queen Theodolinda (589-626) convinced the gens Langobardorum to convert to Christianity, there was a gradual reinterpretation of the rites and gods belonging to the old religiosity. The warrior people of the Longobards worshipped the Norse deity Odin, protector of soldiers and guide of the dead in the afterlife (psychopomp): it was natural, therefore, to recognise this figure in St. Michael the Archangel. After all, he was the one who, with the hosts of angels, defeated the forces of evil by driving them out from heaven1. The centre of the cult was the sanctuary of St. Michael Archangel in Apulia. From here it spread throughout the Italian peninsula. Veneration reached Piedmont through the work of King Grimoald (662-671)2.

The cult of St. Michael was probably also present in Susa Valley, where the archangel was invoked as protector of the fortresses placed to defend the locks of Mont Cenis3. On Mount Pirchiriano, in the Longobard era (6th century), there was a defensive fortress and probably an early chapel dedicated to the saint. It was on this site that one of the most important Michaelic shrines in Europe was to be built: Saint Michael’s Abbey. It represented the first stage of the Via Francigena in Italy, along the variant that crossed the Mont Cenis pass (Via Sacra Langobardorum). The abbey was also located about halfway along the walkway that led from Mont-Saint-Michel in Normandy to the sanctuary of St. Michael the Archangel on Mount Gargano.

The sacred line of St. Michael

It is interesting to note that these three places are located along an ideal straight line that connects seven places of the Michaelic cult4: the monastery of Skelling Michael in Ireland; Saint Michael’s Mount in Cornwall; Mont Saint-Michel in France, Saint Michael’s Abbey in Susa Valley, the Sanctuary of St. Michael on Mount Gargano; the monastery of Symi in Greece and finally the Monastery of Mount Carmel in the Holy Land. According to Christian tradition, the line, known as the “sacred line of St. Michael”, represents the sword stroke with which the Archangel drove the devil back into the underworld.

Certainly, it is possible that the sacred line depends on the number of sanctuaries dedicated in Europe to the Archangel, such that only the most aligned ones are chosen5 – and there are more, such as the Temple of San Michele in Perugia – however, its definition appears remarkable and suggestive.

The building of Saint Michael’s Abbey

Work on the construction of Saint Michael’s Abbey on Mount Pirchiriano began at the end of the 10th century. The hermitage of Giovanni Vincenzo (998) on nearby Monte Caprasio dates back to this period. He had the early Longobard shrine dedicated to the Archangel enlarged. This is witnessed by the monk William, who lived at the end of the 11th century in this coenoby6, in his Chronica Coenobii Sancti Michelis de Clusa.

The legend of the foundation

Like most of the Michaelic shrines in Europe, the Abbey is attributed a legendary origin. According to local tradition, St. Giovanni Vincenzo received an apparition from Archangel Michael7 and wanted to build a chapel on Mount Caprasio, since this was the mountain on which he had withdrawn in prayer. However, from the moment construction work began, a curious fact occurred: the building materials that the saint had collected during the day disappeared during the night. So the hermit decided to keep watch to solve the mystery and, to his amazement, saw a host of angels carrying the material to the summit of Mount Pirchiriano. According to legend, St. Giovanni Vincenzo then realised that this was the place pleasing to God for the building of his House.

The work of Pope Sylvester II and Hugues de Montboissier

The transition from the small monastery of St. Giovanni Vincenzo to the imposing abbey that can be admired today is due to the nobleman Hugues de Montboissier, governor of Aurec-sur-Loire in Auvergne. Apparently, the Frenchman was a spendthrift and to atone for this sinful attitude, he went on a pilgrimage to Rome to meet the pope. By a fortuitous coincidence, the pontiff was also from Auvergne, the name of Sylvester II was Gerbert of Aurillac, and perhaps the two men already knew each other. The pope proposed two alternatives to Hugues: serve his penance with seven years of exile or build an abbey for the Lord. Since the nobleman preferred the second option, Sylvester II entrusted him with the building of a monastery on Mount Pirchiriano.

The choice of place was not accidental. Gerbert of Aurillac had been Giovanni Vincenzo’s successor to the archiepiscopal chair of Ravenna since 998. He was well aware that the hermit was building there a chapel dedicated to Archangel Michael. Between the construction of Giovanni Vincenzo’s monastery and the subsequent expansion, therefore, only a few months passed, since Gerbert of Aurillac became pope in April 999. It is plausible that in the same year Hugues de Montboissier financed the addition of a new coenoby for the monks and for accommodating pilgrims travelling along the Via Francigena.

The successive extensions of Saint Michael’s Abbey

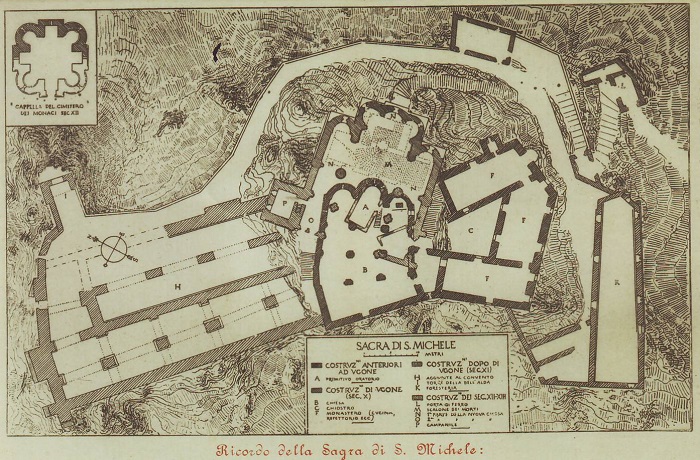

The nobleman entrusted the monastery to Abbot Adverto of Lezat of the diocese of Toulouse and only later to the Benedictines. From this time onwards, numerous extensions and renovations took place, which contributed to the architectural appearance of today’s Saint Michael’s Abbey. In the years between the 12th and 13th centuries, the building of a larger church (1110-1255), based on an old design by the architect Guglielmo da Volpiano, and the so-called “New Monastery” (1099-1390) began. Although it is still possible to fully admire the stylistic mixture of Norman Romanesque and later Gothic additions, little remains of the monastery due to a major renovation in the 13th century. In fact, the complex, which originally included cells, kitchens, a library, workshops and a refectory, fell into ruin due to the passage of French troops in 1629 and the siege of Turin in 1706.

The New Monastery is today only structured in a bare, but fascinating, series of ruins embedded in the mountain. Prominent among them is the Tower of Bell’Alda, so called because, according to a legend, from it a young girl threw herself into the void to escape capture by some mercenaries. So the angels, out of pity, caught her during her flight and gently laid her on the ground. But the young girl, out of vanity to show her friends what had happened, threw herself down again and lost her life8.

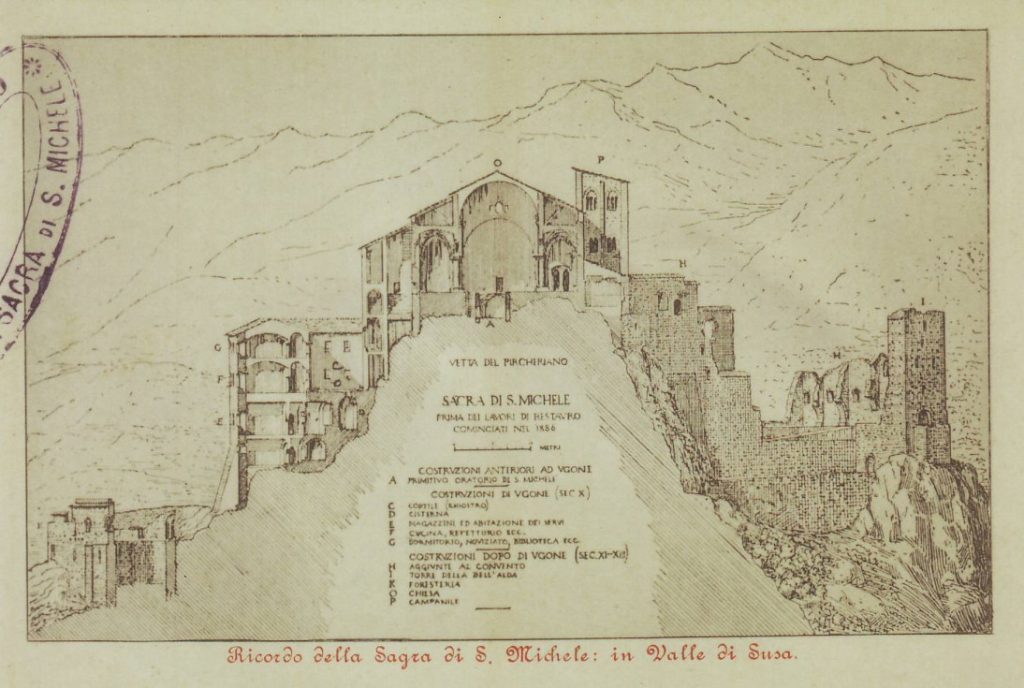

The works by Alfredo d’Andrade

Between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the following century, some consolidation work on the structure became necessary. The architect Alfredo d’Andrade was commissioned to carry out the work, creating the imposing neo-Romanesque rampant arches that run along the southern side of the Abbey. D’Andrade had the merit of ensuring a greater architectural stability by inserting elements in stylistic harmony with the rest of the complex. On the other hand, his intervention altered the original context of some of the rooms and made the stylistic interpretation of the artefacts they contained much more complicated. This difficulty also involved the most important artistic work in the Abbey: the Portal of the Zodiac by the sculptor Niccolò.

Saint Michael’s Abbey between art and symbolism

Two hundred and forty-three steps lead the pilgrim to the vertiginously holy peak, as the peak of Mount Pirchiriano was called by the Rosminian poet Clemente Rebora (20th century). In fact, the summit of the mountain is incorporated in the architectural complex, where it forms the base of one of the supporting columns of the church.

The wayfarer is thus called upon to walk an ascending path, not without fatigue, which has a strong symbolic and spiritual significance. As a mountain, Mount Pirchiriano is above all a sacred center, a place of choice for the encounter with God. The ascending path is, figuratively speaking, the conversion to holiness, which leads man from the materiality of the earth to the gates of Paradise. It is the Holy Ladder of Jacob’s vision9. Even the amount of the steps may not be accidental: the sum of the figures returns the number nine, in the symbolism associated with God and the Trinity.

Terribilis est locus iste! Haec domus Dei est et porta coeli.

How awesome is this place! This is none other than the house of God, and this is the gate of heaven.

Book of Genesis 28, 17

The entrance to Saint Michael’s Abbey

After walking along a pleasant forest path, the Abbey suddenly appears before the pilgrim, enveloped in celestial and mighty austerity. There, we are pervaded by a feeling of uncontrolled vertigo at the sight of the imposing façade. The façade, more than forty metres high, is unusual in its stylistic arrangement. It contains the splayed entrance portal, as one could imagine, but it is surmounted by the apsidal portion of the complex, in a peculiar architectural inversion. An elegant semicircular loggia (“dei Viretti”) rests on the apse, as if it were a celestial crown.

A statue of St. Michael defeating the devil, more than five metres high and sculpted by Paul dë Doss-Moroder, ideally frees the pilgrim about to ascend from evil.

The Staircase of the Dead

After passing through the austere entrance portal, the visitor enters a steep staircase. It runs between the walls of extremely high rooms, decorated with arches and cross vaults. The Staircase of the Dead is situated between the mighty pillars, one of which is more than eighteen metres high, and the ancient rocks. Even the name evocates a spiritual passage: from death to life, from sin to redemption, from earth to heaven. The ascent is steep because the path of conversion is difficult, from one moment to the next one can turn back because of temptation.

From death to life

Until 1936, in the wall niches, along the edges of the staircase and even on the steps, the skeletons of deceased monks and some graves were placed. This explains the name Staircase of the Dead, but also the symbolic meaning of the ascent, the real passage through death.

This staircase is supported by an enormous central pier: here and there the rocks jut out, and portions of sepulchres are dimly seen. At the summit is a great arch, filled with desiccated corpses.

John Murray, Murray’s Handbooks for Traveller, 1847

The Staircase of the Dead did not only have a spiritual function, but its construction was part of the ambitious project for the architectural extension of Saint Michael’s Abbey and served as an access space to the new church that was to be built in the upper part of the sacred building10.

Zodiac Portal

A dazzling light, while rising in the darkness of the Staircase of the Dead, emanates from an opening at the summit. Here a mysterious portal awaits the pilgrim. Along its jambs are carved depictions of the zodiac signs and constellations.

The Portal of the Zodiac is certainly the most famous and important work in Saint Michael’s Abbey. Its reliefs were executed by the Romanesque master Niccolò around 113011, during the time of Abbot Ermengardo, and at least two other sculptors. Through stylistic comparisons, they could be identified as the so-called Master of Rivalta and Pietro di Lione, who had already worked at the cathedral of San Giusto in Susa12. We are certain that the Portal of the Zodiac is the work of Niccolò, since he engraved his name on a jamb. This attests to the exceptional sculptural quality that was desired at Saint Michael’s Abbey. History of art reminds us that Niccolò was one of the most important masters of the Romanesque period, and his work can be found in a number of renowned sites of the time in Piacenza, Verona and Ferrara.

The Portal of the Zodiac is an assemblage of different elements

When tackling the study of the Portal of the Zodiac, we cannot separate the artistic aspect from the symbolic one. This pertains to the mentality of the time in which it was created, when knowledge was interrelated in a unitary conception of reality, and for which there was a close relationship between religion and astrology, knowledge and representation, macrocosm and microcosm. For this reason, it is crucial to examine the work in its original and overall iconographic scheme, and not only in its individual details. However, this is not possible since the Portal we observe today is most likely the result of a posthumous assemblage of different elements. The aforementioned observation can be deduced from marked artistic and architectural anomalies, such as broken lintels, smooth and twisted columns, and capitals of different workmanship.

The most evident peculiarity is that the portal jambs, on which the signs of the zodiac and other constellations are carved, are on the inner part, the side facing the Staircase of the Dead. This is a unusual location, since in the Romanesque style depictions were usually on the outside of portals for symbolic and figurative reasons. Hence, the zodiac reliefs are to be observed according to a logic of a spiritual ascension: they can be interpreted from the inside as they complete the ascent of the Staircase of the Dead and mark the passage between darkness and the open sky of the constellations.

Some doubts in this regard

This interpretation can only be partially true, at most it was the one who reassembled the portal: before d’Andrade’s reinforcement work, it is certain that it led into an enclosed room. All historical traces of this room were lost, and it is not possible to determine whether it was already there when the zodiac reliefs were placed, due to the 20th century renovation work.

[…] two photographic images made around 1907 and taken from the staircase, show us beyond the portal a large quadrangular vaulted room, with an opening axial to that of the Zodiac and surprisingly similar to it in terms of construction scheme and even decorative design.

Daniela Biancolini Fea, in La Sacra di San Michele. Storia. Arte. Restauri, a cura di G. Romano, Torino, 1990. Translation by the author.

The possible original location

Even in a context of historical uncertainty, this raises the doubt that the Portal of the Zodiac was originally located somewhere else. The most significant renovation of Saint Michael’s Abbey in the Medieval period, after the years in which Niccolò worked on it, was the transition from Romanesque to Gothic (13th century). Archaeological excavations carried out by Alfredo d’Andrade led to the discovery of the remains of a pre-existing building with a nave and two aisles and three apses. It is attested that in 1255 the church, rebuilt according to the new style and by reversing the façade, was solemnly consecrated.

It is not difficult to assume that the dismantling of the original portal and its reconstruction in the current location is due to this period. Perhaps it was the entrance portal to the church, located at the highest point of the ascension path, that could justify the theme of the zodiac and constellations. After all, that was probably the privileged point for observing the celestial sphere.

Stylistic homogeneity and cosmic dualism at Saint Michael’s Abbey

It is not even clear if all the constituent elements of the original project were reassembled in the Portal of the Zodiac. However, there is a definite stylistic homogeneity that suggests a common origin. The Portal of the Zodiac consists of two lesenes, which serve as jambs, and seven small columns with capitals. The jambs are decorated on the outside with a cosmological theme with symbols of the signs of the zodiac (right) and other constellations (left). On the inside, however, they show depictions of plant shoots, livestock and human figures.

It is interesting to note the marked symbolic dualism of the lesenes. The right jamb presents the signs of the zodiac inscribed in circular branches: the circle is in fact a figure of the celestial sphere. Conversely, each constellation on the other jamb is inscribed with a plant motif that corresponds to a square. This was, in the Middle Ages, the symbol of the materiality of things and their earthly nature. In essence, the two jambs are meant to represent the concept of the universal whole, in which Christ’s saving work is embedded.

The inscriptions on the jambs

In this regard, by reading the inscriptions that Niccolò carved on the Portal of the Zodiac, it is possible to learn some clues. On the right-hand jamb is inscribed:

- Vos qui transitis sursum vel forte reditis, vos legite versus quos descripsit Nicholaus (You who rise, or by chance descend, read the verses that Niccolò wrote).

On the jamb of the other constellations Niccolò engraved the following words:

- Hoc opus intendat quisquis bonus [exit et intrat]. (Turn your attention to this work whoever, capable, come out and enter). This inscription, incomplete here, is found identical at the cathedral in Piacenza, where Niccolò worked.

- Flores cum beluis comixtos cernitis (Separate the flowers from the beasts). This is probably to be interpreted as an exhortation to separate sins from Christian virtues.

- Hoc opus hortatur saepius ut aspiciatur (This work compels one to observe it repeatedly).

Portal jambs

The right jamb encloses clipeus with depictions of twelve signs of the zodiac and, on the side, the indication of the name in Latin: Chapricorn[u]s; Sagitarius; Scorpius; Libra; Virgo; Leo; Cancer; Gemini; Taurus; Pisces; Aquarius. It is necessary to specify that in antiquity Scorpio and Libra belonged to the same constellation, and therefore here they are depicted together.

The reliefs on the left jamb are carved with the signs of nineteen constellations13 – six from the northern and thirteen from the southern hemisphere – some grouped in the same frame, and also flanked by their names in Latin: Hydra; Ara; Nothius; Cetus; Centaurus; Eridanus; Pistrix; Anticanis; Canis; Lepus; Orion; Deltoton; Pegasus; Delfinus; A[quila]. Not all the names of the constellations are present, the Arrow, Corvus and Crater are to be added, and the topmost relief was unfortunately lost.

A historiographical research

The absence of such a constellation is no insignificant matter, and scholars have long tried to understand its identity. The correct identification of all signs, zodiacal and otherwise, is functional to the symbolic and artistic decipherment of the entire Portal of the Zodiac. A suspicion, later confirmed by historiographical research, is that Niccolò used an ancient astrology manual for the iconographic realisation of the work. This was a common practice in the Middle Ages, and it is likely that the artist had copied the constellations from a volume in the Abbey library at the time.

For a long time this manual was thought to include Aratus’ Phaenomena14, but more recently the inspiration for Niccolò was found in the De Astronomia by Hyginus15. Several copies and versions are known, but one of them, the 11th-century Opusculum de ratione spere, contained in Digby manuscript 83 at the Bodleian Library in Oxford, seems extremely plausible. The Oxford compendium contains all the constellations mentioned by Niccolò in the exact order; moreover, it reveals that the lost relief depicted the sign of the Auriga.

The symbolic motifs of the capitals

Along the inner sides of the Portal of the Zodiac are seven white stone columns, four on the right and three on the left, resting on a base of the same material as the Staircase of the Dead. They most probably belonged to a single figurative scheme as their height (233 cm) and that of the capitals (34 cm) is the same. The sculptures, however, were not all created by the same author, but only a few are of superior quality. One capital showing two quarrels, for example, was probably made by Niccolò – the inscription Hic locus est pacis causas deponite l[itis] invites people to put aside their grudges before entering the church16 – while the others were made by his collaborators.

To the Master of Rivalta are attributed the capital with bicaudate sirens, an admonition against sins of the flesh and perhaps a heritage of ancient pagan fertility cults, and the capital with Samson and Delilah17. On another column are depicted some women suckling snakes, which ungratefully bite their ankles: this is another image of lust18.

The interpretation of the figurative cycle

However, it was suggested that the entire decorative cycle could represent the stories of Samson19, based on the recurrence of the symbolic element of the lion, and other biblical scenes, such as the slaying of Abel. The presence of these Old Testament figures is to be understood as a prefiguration of the coming of Christ. Abel anticipates the theme of the death of the righteous; Samson killing the Philistines, on the other hand, the sacrifice aimed at the salvation of all. The sins, whose representations are set against the left-hand jamb, proper to the dimension of the flesh, are distanced from the salvific work of Christ. It has a cosmological value: the whole Universe is redeemed, both the terrestrial and celestial spheres.

The new church and the vertiginously holy peak

After the Portal of the Zodiac, a short external staircase, crossing the rampant arches by d’Andrade, leads to the so-called “new church”. It is entered through a splayed portal with carved columns and capitals.

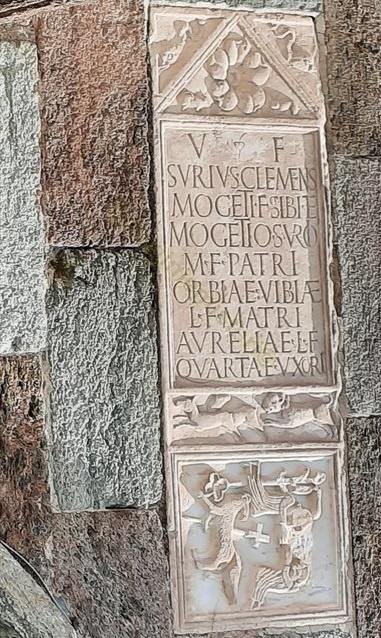

Of particular interest is the effigy of a monk wearing a Phrygian cap. It was perhaps the symbol of the congregation of stonemasons who built the sanctuary. Just above the portal, on the left, is a Roman tomb slab used as reused material. The presence of Christian symbols on it is due to a later addition from the Longobard period.

The interior of the church includes the Old Choir, a vestige of the previous construction phase, and a nave and two aisles without a transept. However, the original roof collapsed in the 16th century. It was replaced by a barrel vault so heavy that it undermined the stability of the building. So it was therefore necessary to build the present cross vault, the work on which was completed in 1937.

The sequence of column and beam pillars at the last two bays, as well as the simultaneous presence of round and pointed arches, demonstrates the gradual transition from Romanesque to Gothic that took place during the 13th century. It is here that at the base of the first pillar on the left is the vertiginously holy peak of Mount Pirchiriano.

A side portal of the church, known as “dei Monaci” (of the monks), leads to a terrace with a view of the valley below. It was in this suspended place that Niccolò, on a night of unprecedented darkness, laid his gaze on the shining of the celestial constellations and glimpsed God.

Samuele Corrente Naso and Daniela Campus

Notes

- Book of Revelation, 12, 7-8. ↩︎

- J. Jarnut, Storia dei Longobardi, Torino, Einaudi, 2002. ↩︎

- P. De Vecchi, Elda Cerchiari, I Longobardi in Italia, in L’arte nel tempo, Vol. 1, tomo II, Milano, Bompiani, 1991. ↩︎

- Kether, La linea del Drago tracciata da San Michele Arcangelo, in L’Archetipo, n. 3, marzo 2018. ↩︎

- St. Michael Alignment is England’s Most Famous Ley Line. But is it Real?, su Big Think, 16 agosto 2011. ↩︎

- I. Aulisa, La Chronica monasterii sancti Michaelis Clusini a confronto con altre tradizioni micaeliche, in “Vetera Christianorum” 33, 1996/1. ↩︎

- Chronica monasterii Sancti Michaelis Clusini. ↩︎

- R. Bordone, La leggenda della bell’Alda, La Sacra di San Michele simbolo del Piemonte europeo, Torino, EDA, 1996. ↩︎

- Genesis 28, 17. ↩︎

- C. Tosco, Nuove ricerche sul Portale dello Zodiaco alla Sacra di San Michele, in “La trama nascosta della Cattedrale di Piacenza, Atti del seminario di studi”, a cura di T. Fermi, Piacenza, 25 ottobre 2013. ↩︎

- E. Pagella, I cantieri degli scultori, in La Sacra di San Michele. Storia. Arte. Restauri, a cura di G. Romano, Torino, 1990. ↩︎

- G. Romano, I cantieri della scultura, in Piemonte romanico, a cura di Idem, Torino, 1994. ↩︎

- S. Lo Martire, Testo e immagine nella Porta dello Zodiaco, in “Dal Piemonte all’Europa: esperienze monastiche nella società medioevale. Relazioni e comunicazioni presentate al XXXIV Congresso storico subalpino nel millenario di S. Michele della Chiusa”, Torino, 27-29 maggio 1985. ↩︎

- C. Verzar, Die romanischen Skulpturen der Abtei Sagra di San Michele: Studien zu Meister Nicholaus und zur “Scuola di Piacenza“, Basler Studien zur Kunstgeschichte, 10, 1968. ↩︎

- Ibidem note 13. ↩︎

- Ibidem note 13. ↩︎

- Ibidem note 11. ↩︎

- J. Leclercq-Marx, La sirène dans la pensée et dans l’art de l’Antiquité et du Moyen Âge: du mythe païen au symbole chrétien, Bruxelles, 1997. ↩︎

- Ibidem note 10. ↩︎