The conquest of Jerusalem, at the end of the First Crusade, marked a fundamental turning point in the history of Medieval Europe. The city had to be defended and preserved, the holy places of Christianity protected by God’s will. Fighting to pray, this was the spirit that inspired the foundation of the Templars: monks and warriors, pilgrims and knights, whose stories still live today as expression of an imaginative and mysterious past.

Historical Preamble

Jerusalem is the navel of the world, […] This royal city, therefore, situated at the centre of the world, is now held captive by His enemies, and is in subjection to those who do not know God, to the worship of the heathens […]. Accordingly undertake this journey for the remission of your sins, with the assurance of the imperishable glory of the kingdom of heaven […] . When an armed attack is made upon the enemy, let this one cry be raised by all the soldiers of God: It is the will of God! It is the will of God!”.

Robert the Monk, Historia Hierosolymitana. Translation by Dana C. Munro, “Urban and the Crusaders”, Translations and Reprints from the Original Sources of European History, Vol 1:2, 1895.

Thus Pope Urban II, during the Council of Clermont in 1095, exhorted the rulers of Europe to prepare an expedition to defend the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem and liberate the city’s holy places from the Seljuk Turks. This was the origin of the Crusades, although it is not certain whether the pontiff’s exhortation really had the bellicose tones reported by later chroniclers. The original meaning was, in fact, that of an iter or sancta peregrinatio, as its purpose was to allow the European faithful to visit Jerusalem. The term ‘crusade’ only appeared after 12501 because of the cross that pilgrims and soldiers had sewn on their chests or cloaks.

Urban II’s request was granted when, in August 1096, a first expedition of the army to the Holy Land took off. On 15 July 1099, after three years of bloody fighting, the Crusaders finally conquered and besieged Jerusalem.

Origins of the Hierosolymitan chivalric Orders

The most difficult mission, however, had just begun. Jerusalem had to be defended and the holy places preserved, especially in a territory far from Europe and surrounded by enemies. To this end, congregations and orders of armed men emerged in the Holy Land from the first years after the conquest of 1099. Their purpose was to guard the Crusader possessions, assist and escort pilgrims on their way to the holy places and ensure supplies from Europe. Among these were the Knights Hospitallers, the Teutonic Knights, the Order of the Canons of the Holy Sepulchre founded by Godfrey of Bouillon, and above all the Pauperes commilitones Christi templique Salomonis (Poor companions in arms of Christ and the Temple of Solomon), more simply known as the Knights Templar.

The Founding of the Order of the Knights Templar

The choice to become a ‘knight of Christ’ in defence of the pauperes Dei and the holy places of Christianity was a true vocation of life. It implied the renunciation of material goods and a complete adhesion to God’s will, as well as an adequate military training. This spiritual call interested even Hugues de Payn, a French knight of the Count of Champagne. He had travelled to the Holy Land a first time for a peregrinatio. When he returned in 1113, he settled definitively in Jerusalem2. Then, after gathering eight other knights, Hugues de Payns took a solemn oath to defend the holy places and the pilgrims who went there. This is a successful historiography by the archbishop William of Tyre about the foundation of the Christi milites3.

William of Tyre and the Historia rerum in partibus transmarinis gestarum

William dates the foundation of the Knights Templar to 1118-1119, but some scholars have contested the veracity of his writings. The archbishop’s writings, therefore, are to be interpreted in a mythical and symbolic sense, in accordance with the Medieval tradition, especially regarding the number of founders of the Order. Moreover, he wrote at least fifty years after the events narrated.

In this same year, [1118] certain noble men of knightly rank, religious men, devoted to God and fearing him, bound themselves to Christ’s service in the hands of the Lord Patriarch. They promised to live in perpetuity as regular canons, without possessions, under vows of chastity and obedience. Their foremost leaders were the venerable Hugh of Payens and Geoffrey of St. Omer.

William of Tyre, Historia rerum in partibus transmarinis gestarum. Translation by James Brundage, The Crusades: A Documentary History, 1962.

Simon of Saint Bertin

Closer in time to the events described is the testimony of Simon of Saint Bertin. The monk reports instead of some (nonnuli) knights who founded the fraternitas, shifting the date of foundation to around twenty years earlier, to 10994.

While he [Godfrey] was reigning magnificently, some [of the crusaders] had decided not to return to the shadows of the world after suffering such dangers for God’s sake. On the advice of the princes of God’s army they vowed themselves to God’s Temple under this rule: they would renounce the world, give up personal goods, free themselves to pursue purity, and lead a communal life wearing a poor habit, only using arms to defend the land against the attacks of the insurgent pagans when necessity demanded.

Simone di san Bertino, “Gesta abbatum Sancti Bertini Sithiensium”, ed. O. Holder-Egger, in Monumenta Germaniae Historica Scriptores. Translation by Helen Nicholson, Documents relating to the Military Orders, 2018

The mysterious figure of Hugues de Payns

There is historiographical uncertainty about the figure of Hugues de Payns. The first written source mentioning the founder of the Templars is the Historia rerum in partibus transmarinis gestarum by William of Tyre. The archbishop refers of a certain Hugo de Paganis, probably a Latin translation of the knight’s name. For a long time, therefore, historians have tried to trace the true identity of this important yet mysterious historical figure.

The most widely accepted theory is that Hugues de Payns was French from the Champagne region. Some important medievalist authors, such as Simonetta Cerrini5 and Marie Louise Bulst-Thiele6 have identified the knight’s origins in a small village, not far from Troyes, called Payns. Hence the derivation of the name by which he is known today, Hugues de Payns. Indeed, some documents from the counts of Champagne and the abbey of Molesmes attest to a knight by this name who had left for the Holy Land around 1113. He was a descendant of the lords of Montigny and a relative of the Montbards, the family of Saint Bernard of Clairvaux. This could explain the choice of Troyes as the seat of the council that approved the Templar Rule, and the presence at the consistory of Saint Bernard himself as guarantor of the Order before Pope Honorius II.

The Italian hypothesis

However, some alternative hypotheses have proposed that Hugo de Paganis is of Italian origin. In the 17th century, Filiberto Campanile7 had identified the knight’s origins near Nocera de’ Pagani, albeit by a posthumous and celebratory reconstruction of the genealogy of the Norman Pagano family.

Recently, it was argued that Hugo de Paganis’ Italian origin is attested by a controversial letter preserved in Rossano, Calabria8. The text, known as the Amarelli Codex, is signed by a man named Ugo de Paganis from Forenza in Basilicata, and is dated October 18, 1103. It reports the death of his cousin Alexander, a member of the Templars, and an oath made by the signer to King Baldwin of Jerusalem.

Although the historical background to which the writing refers seems to be solid, there is only a single copy of that letter dated 1469, whose translation from Latin to Italian is attested by a notary at least two centuries later. These are not sufficient elements to affirm that the letter is a seventeenth-century forgery, perhaps conceived to confer noble rank to the Amarelli family, but certainly an indicative proof. In a suspicious passage, moreover, the text mentions the “velvet” and the “shield” coin, but the medievalist researcher Vito Ricci points out that both were introduced only after the 12th century9.

Finally, the testimony of the seventeenth-century historian, Marco Antonio Guarini, that Hugues de Payns died in 1136 and was buried inside the church of San Giacomo in Ferrara is still to be verified.

At the Temple Mount in Jerusalem

In 1120 King Baldwin II, as gratitude for their services, granted the Knights of Militia Christi the al-Aqsa Mosque at the Temple esplanade in Jerusalem. The area was known to have hosted the ancient Temple of Solomon, hence the name change of the fraternitas to militia Templi. Still after a few years the Templars had no military purpose but merely offered spiritual care and assistance to pilgrims, including hospital care. As such, they resembled the regular canons of the Temple of the Lord and those of the Holy Sepulcher as associated laymen10. It was only later, perhaps to give an explanation of the original meaning of militia, that they detached themselves from the chapter of canons and, in 1120, renewed their vows of obedience, chastity and poverty to the patriarch of Jerusalem, Gormund. They also proclaimed the oath that characterized their vocation from then on:

“Do you also promise to God and to Lady St Mary that you, all the remaining days of your life, will help to conquer, with the strength and power that God has given you, the Holy Land of Jerusalem; and that which Christians hold you will help keep and save within your power?”

And he should say: “Yes, sire, if it please God”.

Paul Hill, The Knights Templar at War, 1120–1312, 2018

De laude novae militiae ad Milites Templi

The idea that a fraternitas of the Church could take up arms certainly faced strenuous resistance. It was an oxymoron: how to reconcile the clergy’s commandments of peace with violence toward one’s neighbor? The criticism, already debated then, was softened only by the intervention of Saint Bernard de Clairveaux, the spiritual father of the time. To the theological uncertainties, which also tormented Hugues de Payns, the saint responded with a writing of fervent encouragement for the Templar mission, known as De laude novae militiae ad Milites Templi. Saint Bernard compared the vauntedness of the Crusader armies, “non militia, sed malitia,” to the holy evangelization work of the Templars. The Order’s mission thus found its symbolic origins in Christ, who had cast out the merchants from the Temple, and the monks’ use of the sword was morally justified by the notion of malicide:

If he kills an evildoer, he is not a mankiller, but, if I may so put it, a killer of evil.

Bernard of Clairvaux, De laude novae militiae ad Milites Templi

The Council of Troyes and the Rule of the Templars

Saint Bernard’s support was crucial for the recognition of the Templars as an order and for them to receive a “Rule”. In 1129, Pope Honorius II convened a council in Troyes, in the cathedral of Saints Peter and Paul. There, with the most important ecclesiastical officials of the time and the abbot of Clairvaux, the Pauperes commilitones Christi templique Salomonis were officially recognized by the Church. The first Rule of the Knights Templar was based on a reworking of the one of Saint Benedict, to whose drafting Saint Bernard had also contributed11.

[…] Then we, in all joy and all brotherhood, at the request of Master Hugues de Payens, by whom the aforementioned knighthood was founded by the grace of the Holy Spirit, assembled at Troyes from divers provinces beyond the mountains on the feast of my lord St Hilary, in the year of the incarnation of Jesus Christ 1128, in the ninth year after the founding of the aforesaid knighthood. And the conduct and the beginnings of the Order of Knighthood we heard in common chapter by the lips of the aforementioned Master, Brother Hughes de Payens.

The Rule of the Templars, The French Text of the Rule of the Order of the Knights Templar, J.M.Upton-Ward, Boydell Press 1997.

Papal concessions to the Templars

In the following years, the Templars obtained enormous privileges by the successive popes, who showed increasing confidence in the Order’s service in the Holy Land. In 1138 Innocent II issued the bull Omne Datum Optimum, which established the spiritual independence of the Templars. Henceforth subject to the exclusive authority of the Pope, they were exempted from paying taxes. Furthermore, the Order was allowed to form its own clerical rank, thus benefiting from apostolic protection and giving history the unmistakable image of warrior monks.

Et, cum nomine censeamini milites Templi, constituti estis a Domino catholice ecclesie defensores et inimicorum Xpisti impugnatores

Also, since you are known by the name of the Knights of the Temple, you were appointed by the Lord to be defenders of the Catholic Church and assailants of Christ’s foes.

Omne Datum Optimum, 1139.

Pope Celestine II’s bull Milites Templi dates back to 1144, by which the Templars were allowed to collect offerings from the faithful12. The following year Eugenius III, through the Militia Dei bull, also granted them the right to collect tithes and organise cemetery services13. Therefore, the Templars could obtain the tax from the so-called donati, small landowners who demanded protection of their property in return.

Life of a knight, among symbols, weapons and prayer

The papal concessions permitted the Templars to become an economic, military and religious power within a few years. The organization of the Order was based on the exploitation of large possessions in Europe, which allowed the sustenance of expeditions to the Holy Land.

As the Order’s economic availability increased, so did the number of military structures, fortifications and castles they owned. In particular, the Templar control over the territory was ensured by structures related to different levels of subordination. The basic unit was the commendam, also known as domus or preceptory: this was the name given to a large property with a castle or cottages and a system of granges, subject to the administrative authority of a bailiff and thus of a province14. Medium-sized fortress-houses, where military training was provided as well as prayer, were instead called captaincies. The services proper to the Templar vocation were carried out at hospitalia, cemeteries and magioni, where pilgrims were welcomed along the main communication routes, such as the Via Francigena. At the top of the political and administrative apex was therefore the Master, magister generalis of the Order.

Within each Templar structure there were different ranks: the noble knights; the servants or sergeants, who came from the less well-off classes; the brothers of the trade, who cultivated the land and did humble work; in each commandery there was also at least one chaplain priest, who was responsible for prayer and wore a rough cloth cloak called bigello.

The Beauceant

Certain customs concerning the clothing and ornaments of the Templars were expressly stated in the Rule. The robes had to be black, white or ash grey. Likewise, a white cloak was provided for the Knights and black for the sergeants. These were the colours that best symbolised the dualism intrinsic in the Templar mission, whose fratres were both monks and warriors, and which also recalled the struggle of good against evil. Indeed, the same tonal contrast can be found in the flag that the Templars held in battle. The Beauceant was the bipartite flag, black and white, that allowed the Knights to recognise each other. Hoisted by a bearer15, it should not fall into enemy hands under any circumstances16 and ideally represented the divine mandate to the Templars’ mission.

The term beauceant was probably to be understood in the etymological meaning of balzana, i.e. a heraldic coat of arms divided into bands. However, it also took on the name Valcento, as the French word Vaucent was affixed to the flag, indicating that each Templar was worth a hundred men. And so, the Knights Templar, following the Beauceant, recited Psalm 113:

Non nobis, Domine, non nobis, sed nomini tuo da gloriam!

Not to us, not to us O Lord, but to Your name give glory

From the prologue of the Rule of Saint Benedict, from which the ‘primitive’ Rule of the Templars is written; the citation is also found in the work De laude novae militiae 13, 31 by Saint Bernard of Clairvaux.

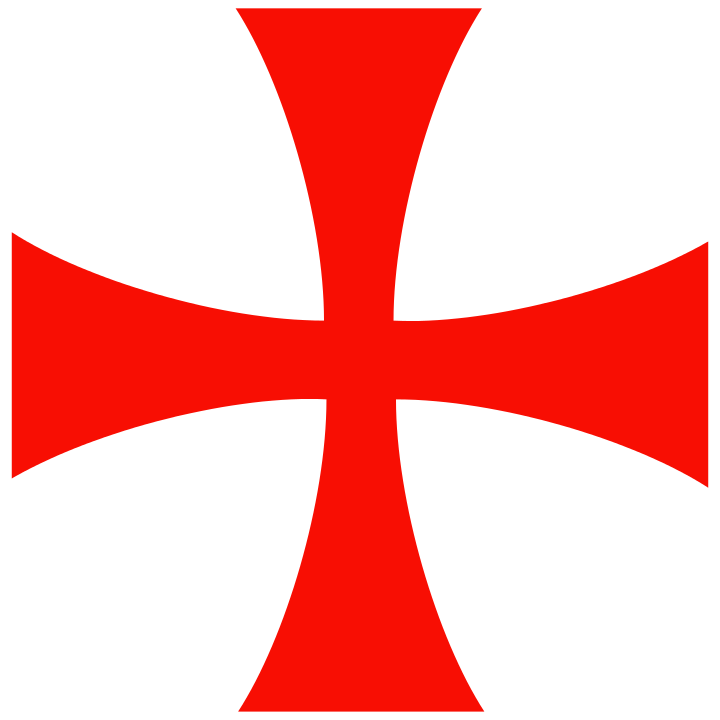

The Cross Pattée

The Templars bore a cross in the upper left-hand corner of their cloaks, in accordance with canonical custom. This symbol originally had no specificity, and the members of the fraternitas themselves were not yet militia, not distinguished in symbolism from all other crusaders. It was only during the Council of Paris in 1147 that Pope Eugene III officially granted the use of a cross patentem. However, a particular cross in use by the Templars is already mentioned in the papal bull Omne datum optimum of 113917:

Cum enim natura essetis filii ire et seculi voluptatibus dediti, nunc, per aspirantem gratiam, evangelii non surdi auditors effecti, relictis pompis secularibus et rebus propriis, dimissa etiam spatiosa via que ducit ad mortem, arduum iter quod ducit ad vitam, humiliter elegistis, atque ad comprobandum quod in Dei militia computemini signum vivifice cruces in vestro pectore assidue circumfertis.

Although you were by nature sons of wrath, committed to the pleasures of this age, through inspiring grace you became attentive hearers of the Gospel, having forsaken worldly ostentation and private property, indeed having abandoned the wide path that leads towards death, you humbly chose the hard way that leads to life and in order to justify being considered among the knighthood of God you always bear on your chest the sign of the life-giving cross.

Omne Datum Optimum, 1139.

The Cross Pattée as a Templar clue

The red Cross Pattée, symbol of martyrdom, was later used in clothing and placed on the Beauceant. It can therefore be said to be unequivocally linked to the Knights Templar, becoming its symbol par excellence in the collective imagination. Nevertheless, this Order did not use it exclusively, nor is it clear whether this concession was also the prerogative of others. It can be argued that the archaeological discovery of a Cross Pattée may constitute a clue – but not a proof – of the Templar presence in a place.

The Templars’ seals

Among the identity symbols of the Knights Templar are the so-called seals. They were obtained by putting the Order’s own stamps on wax or lead. The function of seals was to allow the certain attribution of a letter or document to the sender or issuer. Only a few examples of Templar seals have survived to contemporary historians, although they are highly representative. They were used both by Templar Masters and by individual structures, such as preceptories and provinces. The iconography of the seals pertains to the functions and the missio of the Order.

The most famous stamp is certainly the one bearing on its obverse two knights on a single steed, while the reverse shows a depiction of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. It expresses with great representative force the concept of fraternitas and, at the same time, the militia of the Templars, as well as their place of belonging. This sigillum, which today has become one of the Order’s symbols par excellence in the collective imagination, was used between 1167 and 1250 by the Masters of the time.

However, at a local level, the use of seals by the Templars appears more varied18. Characteristic examples are the seals depicting the Agnus Dei (preceptory of Provence and Aragon, 1224); an eagle with spread wings grasping a snake with its beak (various German preceptories); the Cross Pattée (Aquitaine preceptory, 1251-1307); a pelican feeding its young by pecking at its breast (Arles Temple House); and the unicum of Saint George fighting the dragon (French preceptory, 1255).

Templars symbolism

Besides the well-known symbols historically used by the Templar Order, there are others that were associated to them. Firstly, there is an important parallelism between the Beauceant’s black and white contrast with the chessboard. It is not excluded that it was the Templars themselves who contributed to the spread of the game of chess, originally from the East, in Europe.

Furthermore, the place where the knights were stationed has triggered multiple research and symbolic interpretations. Thus, the discovery of a Solomon’s Knot, a Sacred Centre, or a Merels Board – the original architecture of the Temple of Jerusalem – is traditionally associated with the Templars, albeit with historiographical uncertainty.

The last bastion

After Hugues de Payns’ death in 1136, the Templars continued their military and political activities for about two centuries. The founder of the Order had inaugurated the long tradition of Masters, which continued with Robert de Craon and twenty-one others. The Knights Templar only left the Holy Land after the conquest of Acre, the last coastal stronghold of the Crusaders. In fact, the Mamluks had laid siege to the city, conquering it in 1291.

This event decreed the failure of the Christian Crusades in the Middle East and of the mission for which the Order of the Temple had been established. The last Templar master, Jacques de Molay, did not fully understand the geopolitical turn of events. Unlike the Knights of Malta in Rhodes, for example, he lacked the saving intuition to reconstitute the Templars as a sovereign state. This is the reason why the political-religious crisis between Philip the Fair and Clement V mainly affected the Order, now deprived of its original function and which had accumulated enormous wealth over the years.

The Templars’ Treasure

Thanks to the possibility of collecting the tithe of missions and the exemption from taxes, since the concessions of the bull Omne Datum Optimum of 1138, the Order of the Temple became extremely wealthy. The Templars were a true economic power in Medieval Europe, contributing to social life, through their well-known assistance, hospitable and cemetery services, as well as to politics. They were also responsible for the construction of a great number of civil and religious buildings through funding and labour.

The sacred relics of Christianity

The enormous wealth accumulated by the Order has given rise to numerous legends throughout history. Among these, the tales connected with the Templars’ priceless treasure, which is said to have included some precious relics of Christianity. In the ruins of the ancient Temple of Solomon, the knights are said to have found, for example, the Ark of the Covenant with the Tablets of the Law of Moses.

Another legend, originating in the same Medieval literary tradition19, tells of the discovery of the Holy Grail, the chalice that collected the blood of Christ dying on the cross and from which he had drunk during the Last Supper. Also linked to this tale is the tradition of the sacred Spear of Longinus, which the Roman soldier used to pierce the side of the crucified Christ. Peter Bartholomew, during the First Crusade, claimed to have found the relic in Antioch, following a mystical vision20, but the authenticity of the find was disputed at the time.

What is certain, however, is that the Templars used to carry into battle a fragment of wood believed to be from the True Cross21. According to tradition, the relic was found in Jerusalem by Saint Helena, who had it transported to Constantinople22.

The process against the Templars

At the end of the Crusades, the situation of the Church was undergoing great instability. Pope Boniface VIII, born Benedetto Caetani, had shown an authoritative and determined character since his election to the papal throne in 1294. After the unfortunate period of Celestine V, once again a pope sought to reaffirm the temporal power of the Church and the primacy of Peter over all of Europe. Nevertheless, in pursuing his policy, Boniface soured relations with the Roman noble families, including Colonna family, and especially with the king of France, Philip the Fair. The tensions culminated in the outrage known as the slap of Anagni by Sciarra Colonna against the pontiff. Thirty-four days later Boniface VIII died, leaving the seat to his successor Clement V.

In the meantime, Philip the Fair had openly opposed the authority of the papacy, threatening to declare Boniface VIII a heretic and occultist and to provoke a schism of the transalpine church. Pope Clement V chose to resolve the tensions by making compromises with the French king. In exchange for a promise not to conduct a post mortem trial against his predecessor, he initiated an enquiry against the Templars in April 1307.

The enquiry and capture of the Templars

The judicial purpose was to investigate the alleged accusations of heresy, sodomy and idolatry levelled against the Order. These were defamatory statements made by Philip the Fair, who was undoubtedly aiming to take possession of the huge Templar treasure23. Indeed, the investigations were still not completed when, on 14 September of the same year, the sovereign arrested all Templars in France and ordered the confiscation of their property. For his part, Clement V did not oppose and confirmed the condemnation with the bull Pastoralis praeminentiæ in November24. The French influence on the papacy proved so preponderant that Clement decided to transfer the Holy See to Avignon in 1309. This historical period, which lasted until 1377, is known as the Avignon Papacy.

The accusations

It is historically proven that the accusations levelled against the Templars were instigated by Philip the Fair, who aimed at their dissolution. They concerned the most disreputable actions that a Christian could commit. The members of the Order were thus accused of worshipping a bearded pagan idol called Baphomet, of spitting on the cross, and of committing obscene acts. Nevertheless, it is necessary to filter the accusations in the light of two relevant considerations. Firstly, certainly there were some Templars who had indeed committed such sins in the past, but who had converted in the meantime. Moreover, we should not underestimate the power of torture to force people to confess even untrue things

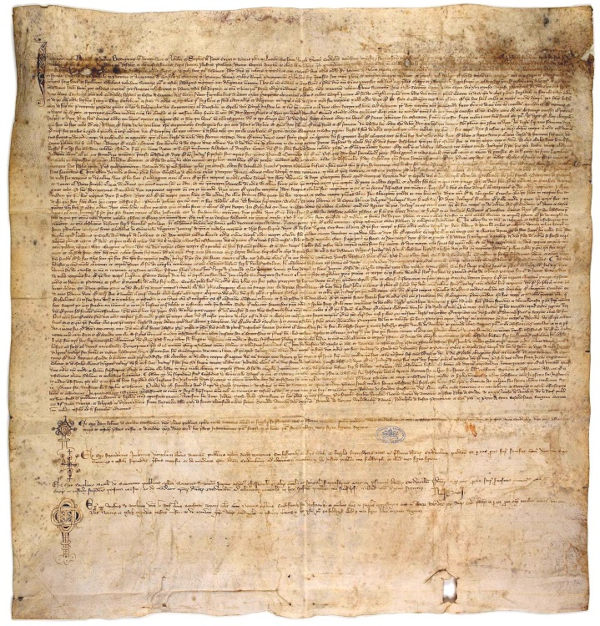

However, when Philip the Fair confirmed the condemnation in Tours (1308), Clement V restarted his investigation, sending two cardinals to Chinon, where most of the Templar dignitaries were imprisoned. The acts of the process are collected in an important historiographical document known as the Chinon Parchment. It represents a cross-examination of the few members heard, including Jacques de Molay, and surprisingly reveals that they were acquitted.

The Chinon Parchment

At the Vatican Apostolic Archive, historian Barbara Frale found a fundamentally important document in 2001. It, called the Parchment of Chinon25, shows that Pope Clement V had withdrawn the charges against the Templars just a year after issuing the bull Pastoralis praeminentiæ. The text, thought to be lost for about seven hundred years, was incorrectly inventoried and bears the date 17-20 August 1308. It was drafted by the apostolic notary Robert de Condet.

The Chinon Parchment is the written summary of the enquiry that Clement V had initiated to discover the truth about the Templars. The process took place in the castle of Chinon, in the diocese of Tours, hence the name of the document. During it, the leaders of the Templar Order were interrogated, including Grand Master Jacques de Molay, who was heard as the last.

“After this, we concluded to extend the mercy of pardons for these acts to Brother Jacques de Molay, the Grandmaster of the said Order, who in the form and manner described above had denounced in our presence the described and any other heresy, and swore in person on the Lord’s Holy Gospel, and humbly asked for the mercy of pardon [from excommunication], restoring him to unity with the Church and reinstating him to the communion of the faithful and the sacraments of the Church.”

Archivum Arcis Armarium D 217, Chinon Parchment dated August 17–20, 1308.

Consequences

The defendants denied the charges against them and the investigation thus ended with the pope’s absolution of the Order. With this act, Clement V perhaps hoped to save the members of the Templars from the persecution that Philip the Fair was perpetrating against them. Although this act of clemency did not fully achieve its purpose – Jacques de Molay was burned at the stake on 18 March 1314 – it allowed many to be welcomed back by the Church, joining other congregations and having their lives saved. This contributed to the flourishing of numerous legends according to which the Templars did not dissolve at all but, taking refuge in a safe place, continued to guard the enormous treasure accumulated over the centuries.

The trial against the Templars

However, while Clement V granted the indulgence at Chinon to some people, he convened the papal commission in Paris to judge the work of the entire Order. Furthermore, with the bull Faciens misericordiam of 12 August 1308, the pope revitalised the process against the Templars, ordering its prosecution during a council in Vienne. The consistory began on 16th October 131126 with the pope and a Templar delegation in attendance, who tried to dismantle the accusations. Nevertheless, Philip the Fair, in order to turn the judicial outcome in his favour, marched with his army to Vienne. Clement V could only decree the dissolution of the Templar Order with the bull Vox in excelso (22 March 1312), not with a formal condemnation but, because of the accusations, administratively27.

Templars’ dissolution

The persecution of the Templars, which was followed by a damnatio memoriae, was a purely political act. The dissolution of the Order was for Philip the Fair the necessary solution to avoid the bankruptcy of the Kingdom of France. Finally, the Church disbanded the Templars between 1312 and 1314. The bull Considerantes dudum of 6 May 1312 decreed freedom for the innocent and for those who had admitted guilt, while it ordered the burning of the condemned and those who had retracted their confession28.

On 11 March 1314, in front of Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris, a papal commission read out the sentence of life imprisonment for the last Templar Master Jacques de Molay and the preceptor of Normandy Geoffrey de Charnay, who had confessed to the charges. But faced with the prospect of being imprisoned for life, they retracted their statement, claiming that they had lied to the inquisitors because they were forced to by torture29.

“when the cardinals believed that they had imposed an end to the affair, immediately and unexpectedly two of them, namely the grand master and the master of Normandy, defending themselves obstinately against the cardinal who had preached the sermon and against the archbishop of Sens, returned to the denial both of the confession as well as everything which they had confessed”

Guillaume de Nangis, Chronicon30, translation by Michael Haag, The Tragedy of the Templars: The Rise and Fall of the Crusader States, 2012

Hence Philip the Fair, as the matter was now within the jurisdiction of French justice, condemned them to be burned at the stake. The execution was carried out on an island in the Seine, known at the time as the Jews’ island.

The Curse of Jacques de Molay

A witness to the events narrated, Godefroy de Paris, transcribed Jacques de Molay’s last words before the pyre31:

“Lessiez-moi joindre I po mes mains, et vers Dieu fere m’oroison; car or en est temps et seison. Je voi ici mon jugement, où mourir me couvient brément; Diex set qu’à tort et à péchié. S’en vendra en brief temps meschié sus celz qui nous dampnent à tort: Diex en vengera nostre mort.

“At least let me join my hands a little and make a prayer to God for now the time is fitting. Here I see my judgement

Godefroy de Paris, Chronique métrique (1312-1317). Translation by Alain Demurger, The Last Templar: The Tragedy of Jacques de Molay, Last Grand Master of the Temple. 2009

when death freely suits me; God knows who is in the wrong and has sinned. Soon misfortune will come to those who have wrongly condemned us: God will avenge our death”.

Jacques de Molay’s last speech, with his dignity in front of death, shook the consciences of his contemporaries. The opinion that he had cast a terrible curse to Clement V and Philip the Fair inspired a centuries-old legend. The belief that the Templars and Jacques de Molay had been unjustly condemned became a certainty when the Pope died in April of the same year 1314, and the King passed away just six months later.

Samuele Corrente Naso

Notes

- J. Flori, Pour une redefinition de la croisade, in Cahiers de civilisation médiévale, 47e année, n.188, 2004. ↩︎

- F. Cardini, Simonetta Cerrini, Storia dei Templari in otto oggetti, 2019; Franco Cardini, I templari, Giunti, 2011. ↩︎

- Guilelmus Tyrensis, Historia rerum in partibus transmarinis gestarum: “Eodem anno quidam nobiles viri de equesti ordine, deo devoti, religiosi et timentes deum, in manu domini patriarche Christi servicio se mancipantes, more canonicorum regularium in castitate et obedientia et sine proprio velle perpetuo vivere professi sunt. Inter quos primi et precipui fuerunt viri venerabiles. Hugo de Paganis et Gaufridus de Sancto Aldemaro”. ↩︎

- Simone di San Bertino, Gesta abbatum Sancti Bertini Sithiensium, ed. O. Holder-Egger, in Monumenta Germaniae Historica Scriptores. ↩︎

- P. V. Claverie, S. Cerrini, La révolution des Templiers. Une histoire perdue du XIIe siècle, Paris, 2007. ↩︎

- M. L. Bulst-Thiele, Sacrae Domus Militiae Hierosolymitani magistri: Untersuchungen z. Geschichte d. Templerordens 1118/19-1314, Gottingen, 1974. ↩︎

- F. Campanile, L’armi, overo insegne de’ nobili, Napoli, Tarquinio Longo, Napoli, 1610. ↩︎

- Libro nel quale si dimostra la nobiltà dell’antica famiglia Amarelli della Nobilissima Città di Rossano in M. Moiraghi, L’taliano che fondò i Templari, Ancora, 2005. ↩︎

- V. Ricci, Hugo de Paganis: champenois o lucano? Un falso problema, in Il Giornale di Napoli, 26 gennaio 2018. ↩︎

- Ibidem note 2. ↩︎

- Dalla regola dei Templari, 1129: “Nos ergo cum omni granulazione, ac fraterna pietate precibusque Magistri Hugonis, in que prӕdicta militai sumpsit exordium, cùm Spiritu Sancto intimante ex diversis ultramontanӕ provinciӕ mansionibus, in solemnitates S. Hilarij, anno 1128 ab incarnato Dei folio, ab inchoatione prӕdictӕ militiӕ nono, ad Trecas, Deo Duce, in usum convenimmo, et modum, et observantiam Ordinis Equestris per singola Capitula, ex ore ipsius prӕdicti Magisteri Hugonis audire meruimus, ac iuta notitiam exiguitatis nostrӕ scientiӕ, quod nobis videbatur bonum, et utile, collaudavimus“. ↩︎

- M. Barber, La storia dei Templari, traduzione di Mirko Scaccabarozzi, Piemme, 2003. ↩︎

- A. Demurger, Les Templiers, une chevalerie chrétienne au Moyen Âge, Seuil, 2008. ↩︎

- J. Riley-Smith, Knights of St. John in Jerusalem and Cyprus, Londra, 1967. ↩︎

- M. Melville, La vie des Templiers, ed. Gallimard, 1974. ↩︎

- J. P. Bourre, Dictionnaire templier, ed. Dervy, 1995. ↩︎

- Ibidem note 2. ↩︎

- G. C. Bascapè, Sigillografia. Il sigillo nella diplomatica, nel diritto, nella storia, nell’arte, volume II, Fondazione italiana per la storia amministrativa, Milano 1978. ↩︎

- Jacopo da Varazze, “Legenda Aurea“, 1260-1298; Robert de Boron, “Roman dou l’Estoire de Graal ou Joseph d’Arimathie”, XIII secolo. ↩︎

- R. Steven, A History of the Crusades, vol. 1: The First Crusade and the Foundation of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, Cambridge University Press, 1987. ↩︎

- P. P. Read, The Templars, St. Martin’s Press, New York, 1999. ↩︎

- Teodoreto, Storia ecclesiastica; Rufino, Storia ecclesiastica; Socrate Scolastico, Storia ecclesiastica; Sozomeno, Storia ecclesiastica. ↩︎

- Ibidem note 2. ↩︎

- Ibidem note 13. ↩︎

- B. Frale. Il Papato e il processo ai Templari. L’inedita assoluzione di Chinon alla luce della diplomatica pontificia, Viella, 2003. ↩︎

- Ibidem note 13. ↩︎

- Ibidem note 2. ↩︎

- Ibidem note 13. ↩︎

- Ibidem note 13. ↩︎

- Ibidem note 12. ↩︎

- N. de Wailly, L. Delisle, Chronique rimée attribuée à Geffroi de Paris, ‘Recueil des historiens des Gaules et de la France’, Parigi, 1860. ↩︎