Sacred vessel, mystical object of faith, but also magic stone, treasure of knowledge, heart of man: what the Holy Grail is, no one can know. It eludes the intellect, as only mystery can. Many are those who have undertaken its search, always following faint traces, as elusive as the enchantment of a legend on the edge of twilight. The Grail belongs to a borderline dimension between the knowable and the arcane, between matter and idea. Like a mirror, it is a myth that reflects reality. Like a tale it embellishes it, distorts it so that it becomes inaccessible to man. “The quest of the Holy Grail is the search for the secrets of God, unknowable without grace”, wrote Étienne Gilson1, thus expressing its transcendent essence.

Holy Grail literature

There is no Grail, therefore, without an inner quest, without a revelatory question that discloses the path to righteousness. So it is for Chrétien de Troyes’ Perceval2, an unwitting anti-hero who arrives at the court of the Fisher King, a sick sovereign whose kingdom is in ruins. There, the young knight witnesses a mysterious scene: a valet carries a bleeding spear, but above all a “graal antre ses deus mains une dameisele tenoit“. A grail between his two hands a lady held. But Perceval could not know that the king’s recovery was linked to that object. Only he who, with a pure heart, had asked the cup function would have freed him from the disease. But Perceval chose instead the silence of courtesy, and thus condemned the Fisher King to his infirmity forever.

“And the boy watched them, not daring to ask why or to whom this grail was meant to be served, for his heart was always aware

Chrétien de Troyes, The story of the Grail, translation by Burton Raffel

f his wise old master’s warnings. But I fear his silence may hurt him, for I’ve often heard it said that talking too little can do as much damage as talking too much. Yet, for better or worse, he never said a word”.

The Perceval of Chrétien de Troyes

Le Roman de Perceval ou le conte du Graal by the Frenchman Chrétien de Troyes, written between 1175-1190 for Philip of Alsace, Count of Flanders, and left unfinished, is the first literary attestation of the Grail. The tale enjoyed enormous fortune in the years to come. Numerous authors have taken up the theme, trying to complete it. There are at least four apocryphal continuations. The Grail narrated by Chrétien de Troyes, however, still lacks the historical attributes it will later possess. The author refers, in fact, to a grail, i.e. a generic flat-shaped vessel. This fact can be deduced from the etymology of the French term, which is based on the Medieval Latin gradalis3.

It is still a cup that “it glowed with so great a light that the candles suddenly seemed to grow dim, like the moon and stars when the sun

appears in the sky” and which “was made of the purest gold, studded with jewels of every kind, the richest and most costly found on land or sea”4. Perceval’s Grail has already a divine power and the tale reveals that it contains a sacred host. This was the only material food of the Fisher King’s father.

“But don’t imagine it holds salmon and pike and eels! A single sacred wafer is all it contains, and it keeps him alive and gives him comfort, so holy a thing is that grail”.

Chrétien de Troyes, The story of the Grail, translation by Burton Raffel

The sainte chose

In Chrétien de Troyes, the sainte chose is thus the content of the Grail. It is not the vessel, which corresponds to an everyday object. But the mysterious Grail is there for a reason. It must arouse Perceval’s curiosity so that, through questioning, he can grow as a man. The message Chrétien de Troyes wants to leave to posterity is social, anthropological. The Fisher King’s infirmity is a metaphor expressing the evil of his time. This is the vacuity of chivalrous values for their own sake, of human actions conducted without divine Grace. Perceval is indeed mute because he is a slave of sin. He has to overcome numerous trials, undergoes a personal maturation for understanding the values of reason, courtly love and loyalty in battle, to receive Christian revelation. The hero has to abandon the vices of worldly chivalry to embrace the holy principles of heavenly chivalry.

The Celtic origins of myth

Chrétien de Troyes seems to draw from ancient reminiscences of Celtic mythology5 and, in particular, from that subject of Brittany that had spread in the preceding decades. Geoffrey of Monmouth, in his Historia Regum Britanniae, had already legitimised the mythical ancestry of the Breton kingdom: Arthur is the legendary Celtic hero who dominates the Saxons at the fall of Rome. Regardless of the political interpretations underlying the work – Geoffrey is writing at the court of the House of Plantagenet- we see here a narrative continuity of the consistent pre-existing tradition.

The Cauldron of Dagda and the Spear of Lugh were some of the treasures that, it was believed, the legendary Túatha Dé Danann ancestors brought with them to Ireland when they colonised this land6. The vessel of the Celtic god, in particular, already bore the attributes that would be proper to the Grail, as the dispenser of abundance, knowledge and even resurrection to the dead in battle7. The magic spear, on the other hand, never stopped bleeding. This is what Perceval saw in the castle of the Fisher King.

In the Irish tales, finally, the Túatha Dé Danann possessed two other treasures, which were called the Sword of Light and the Stone of Destiny8; these magical objects would inspire later works of Grail literature. The symbol of the former will recur, in particular, throughout the Arthurian cycle: in Robert de Boron’s Merlin (early 13th century), the young Arthur becomes king when he draws a sword from the stone9.

Von Eschenbach’s Parzival and the lapis exillis

A few decades after the work of Chrétien de Troyes is the Parzival by Wolfram von Eschenbach (1200-1205). The German author draws on the chivalric tales of the time, but reworking them in a critical manner. Von Eschenbach’s work, the first true bildungsroman in German literature, also remakes Chrétien de Troyes’ Perceval. He traces some passages from it, albeit with new narrative cues. At the same time, he wants to distance himself from it, perhaps to claim the originality of his writing:

“If master Cristjan, born at Troys, impaired this tale with some alloy, Kyot then may justly rail, for he has told the authentic tale […]. From Provence into Germany The story came, told properly, complete unto its very end. No more I say, nor more intend – Wolfram von Eschenbach by name – than was my master Kyot’s aim”

Wolfram von Eschenbach, Parzival, translation by Edwin H. Zeydel and Bayard Quincy Morgan

We will not discuss the differences between the writings of the two authors, but will focus on the Grail. In von Eschenbach it is not a dish, but a stone with miraculous powers10, the lapsit exillis. A lot of discussion has taken place about this term, which most people derive from the Latin lapis ex coelis. A jewel that fell from heaven, therefore, during the battle between Lucifer and the heavenly army of the archangel Michael.

“When in belligerent action Lucifer fought the Trinity, whate’er of angels one could see, the noble and the worthy, must share existence earthy in service of the Holy Grail”

Wolfram von Eschenbach, Parzival, translation by Edwin H. Zeydel and Bayard Quincy Morgan

The Templars of von Eschenbach

Even von Eschenbach’s Grail has no Christological or indeed mystical attributes. It is a mere object whose function is to provide the necessary nourishment for his owners, ensuring eternal youth. The spiritual element, as in Chrétien de Troyes, comes from divine intervention, it is not intrinsic to the Grail. Thus we read that a dove, on Good Friday, placed a consecrated host on it. The guardians of the sacred stone are the “Templars”. This is a name evocative of the famous chivalric Order of Jerusalem, but the association is far from proven. It is possible that von Eschenbach simply wanted to attribute the custody of the Grail temple, i.e. the Munsalwaesche castle11, to these knights. This was the home of the Fish King Anfortas, whose name deliberately recalls the Old French enferté, i.e. infirmity.

“[…] many doughty warriors dwell around the Grail at Munsalvaesch’. They often seek adventure fresh as chivalrous exemplars,

Wolfram von Eschenbach, Parzival, translation by Edwin H. Zeydel and Bayard Quincy Morgan

and all these many templars no victory or defeat may win […] By a wondrous stone they’re nourished whose purity e’er has flourished. If you’ve no information I’ll give you its appellation: ‘Tis called the lapsit exillis. […] This is the stone men call the Grail. […] Good Friday ’tis, as I have said, and there they now observe o’erhead a dove from heaven winging, that to the Grail is bringing a

wafer white and full of grace which on the stone the dove will place”.

The saving question

Von Eschenbach completes the story of Parzifal, unlike Chrétien de Troyes’ unfinished work. Here a wise hermit, his uncle Trevrizent, reveals to the knight the mistakes he has committed, above all the silence. As in the French novel, the Fisher King can recover from his infirmity by listening to the Grail question. Nevertheless, Parzifal prefers to keep silent. He merely observed that strange procession in which a maiden, Repanse de Schoie (‘thought of happiness’), holds the lapsit exillis. Parzifal must therefore make up for the nefarious shortcoming. So having set out in search of the Grail and having once again come before Anfortas, he finally asks the king the saving question “Uncle, what ails you?”, thus becoming himself the heir to the throne.

Robert de Boron and the chalice of Christ

The Grail as we imagine it today, as the chalice Christ used during the Last Supper, is the result of the work by Robert de Boron, and in particular of what is narrated in his trilogy Le livre du Graal (1191-1212)12. In the first part of the account, the Joseph d’Arimathie, Robert de Boron reveals that the relic corresponds to the chalice used by Christ, at Simon’s house, during the Last Supper.

Then he took a cup, gave thanks, and gave it to them, saying, “Drink from it, all of you, for this is my blood of the covenant, which will be shed on behalf of many for the forgiveness of sins. I tell you, from now on I shall not drink this fruit of the vine until the day when I drink it with you new in the kingdom of my Father”.

Gospel of Matthew 26, 27-29

The Joseph d’Arimathie

The author introduces the figure of Joseph of Arimathea into the literary cycle. He was certainly inspired by a 2nd century apocryphal text known as the Gospel of Nicodemus. Joseph is in the canonical gospels a member of the Jerusalem Sanhedrin. Above all, he is the one who deposes Christ from the Cross. According to De Boron’s account, Pilate gave the sacred chalice to Joseph of Arimathea. The saint collected in it the blood of the Son of God that Longinus had gushed out with his spear. Joseph thus became the first guardian of the Grail. It was Jesus himself who confirmed this to him in a vision:

“And Our Lord replied: ‘Joseph, you must be its keeper, you and whoever else you may command. But there must be no more than three keepers, and those three shall guard it in the name of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit – and you and all who guard it must believe and know that these three powers are one and the same being in God”.

Robert de Boron, Le livre du Graal, translation by Nigel Bryant. In: Merlin and the Grail: Joseph of Arimathea, Merlin, Perceval: the trilogy of prose romances attributed to Robert de Boron, D. S. Brewer Woodbridge, UK, Rochester, NY, 2005.

The Grail as a Christian relic

So, Robert de Boron lays the foundation for the successful literary topos that has come down to the present day. The Grail becomes the relic par excellence, a sacred heirloom of inestimable value that encapsulates the very essence of Christianity. Indeed, the chalice is a Eucharistic sign. It is the tool with which Christ, on the evening of Holy Thursday, had announced the mystery of redemption.

“Those who wish to name it rightly will call it the Grail, which gives such joy and delight to those who can stay in its presence that they feel as elated as a fish escaping from a man’s hands into the wide water.”.

Robert de Boron, Le livre du Graal, translation by Nigel Bryant. In: Merlin and the Grail: Joseph of Arimathea, Merlin, Perceval: the trilogy of prose romances attributed to Robert de Boron, D. S. Brewer Woodbridge, UK, Rochester, NY, 2005.

That is why Joseph of Arimathea must officiate daily at the Grail service, a representation of the Last Supper.

The Merlin and the Perceval

Robert de Boron’s Le Livre du Graal continues with Merlin and then Perceval. Here we find many elements that characterize the literary cycle of Brittany. Thus, Merlin has the task of handing down the events of the Grail to posterity and to kings. It is he who establishes the Round Table for the most valiant knights. However, one place must remain vacant. It corresponds to that occupied by Judas at the Last Supper, and on which a terrible curse hangs. Nevertheless Arthur, having become king after drawing his sword from the rock, allows Perceval to sit on the vacant seat. At that moment a chilling scream rises among the knights and the stone of the Round Table cracks. The kingdom of Arthur will have no peace until Perceval finds the Grail and heals the Fisher King its guardian!

“When such a knight is exalted above all other men and is counted the finest knight in the world, when he has achieved so much, then God will guide him to the house of the rich Fisher King. And then when he has asked what the Grail is for and who is served with it, then, when he has asked that question, the Fisher King will be healed, and the stone will mend beneath the place at the Round Table, and the enchantments which now lie upon the land of Britain will be cast out”.

Robert de Boron, Le livre du Graal, translation by Nigel Bryant. In: Merlin and the Grail: Joseph of Arimathea, Merlin, Perceval: the trilogy of prose romances attributed to Robert de Boron, D. S. Brewer Woodbridge, UK, Rochester, NY, 2005.

The Queste of the Holy Grail: the Breton cycle

With Robert de Boron’s work, reality and myth merge. If the Grail was indeed the sacred chalice of the Last Supper, if it had received the blood of the son of God, then it must surely possess exceptional powers, and whoever found it would receive the gift of eternal life…

The Grail transcends, then, from a mere object to an eschatological metaphor. It becomes the image of divine grace redeeming humanity. Salvation of the soul, however, is a gift that belongs to the deserving man. Only those who pursue virtue can attain eternal life. Beginning in the 13th century, a wide strand of tales centered on the quest for the Grail developed. Such is the Quest of the valiant knight, embodiment of the Medieval hero who, in seeking the sacred chalice, is called upon to find himself first and foremost.

The French novels of Lancelot in prose, and the Arthurian cycle in its entirety, fully express this moral order, which belongs to the Cluniac and Cistercian monastic circles of the time. The flourishing of the multiple fantastic narratives is an expression of a disruptive religious feeling, which elevates the spirit of man through the fulfillment of a missio: Arthur pulls the sword from the stone, Lancelot frees Guinevere from the dungeon of Meleagant Castle, the Knights of the Round Table undertake the Quest of the Holy Grail. It is on the basis of this substratum that the Englishman Thomas Malory will finally write The Death of Arthur (about 1485). Perhaps it is the novel that has most contributed to imprint the events of the Grail in the collective imagination.

The historical search for the Grail

Based on the broad literary strand developed from the 13th century onward, which identified the Holy Grail with the chalice of Christ, the Quest is similarly transposed to the real level. If the relic, in fact, corresponds to an object that really existed, why not try to find it? This, in essence, is the idea that inspired the historical search for the Grail. Of course, it is easy to see how tenuous the traces of a relic dating back two thousand years can be. Especially in the historiographical and archaeological fields. That is why there are many leads, parallel investigations, all of them somewhat likely. Nevertheless, if each of the Grail seekers were telling the truth, we would have not one but hundreds of Grails.

The Holy Grail in Jerusalem

According to the canonical Gospels, written in the second half of the first century, when Christ was crucified the Grail was in Jerusalem, the holy city where the Last Supper with the apostles took place. A search for the Holy Chalice that wants to call itself historical should logically begin here, but there is no mention of such an artifact except in a seventh-century source13. A chronicle of the pilgrim Arculf, who was on his way to Jerusalem from the British Isles, stated that:

Between the basilica of Golgotha and the Martyrium, there is a chapel in which is the chalice of the Lord, which he himself blessed with his own hand and gave to the apostles when reclining with them at supper the day before he suffered. The chalice is silver, has the measure of a Gaulish pint, and has two handles fashioned on either side … After the resurrection the Lord drank from this same chalice, according to the supping with the apostles. The holy Arculf saw it, and through an opening of the perforated lid of the reliquary where it reposes, he touched it with his own hand which he had kissed.

Richard Barber, The Holy Grail: imagination and belief, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 2004.

On closer inspection this is a very weak historical clue: Arculf’s testimony is much later than Christ’s Passion. Further, we have no other evidence to ascertain that the chalice seen by the bishop was indeed the original one. Nor is there any mention of such a relic later, a fact that is at least suspicious. Moreover, if indeed the Grail had been silver, as described in the story, we would certainly have found evidence of it in the aforementioned literature and chivalric novels.

The Sacred Basin of Genoa

It is interesting to note the choice of Chrétien de Troyes and later authors to describe a Grail composed of jewels, especially emerald. There certainly was an oral tradition linking the holy relic to such a gem, and perhaps even a historical basis. William of Tyre tells of the discovery of a precious emerald vase (“vas coloris viridissimi, in modum parapsidis formatum”) by William the Drunkard’s Genoese troops during the siege of Caesarea in 110114. For the Archbishop of Toledo Rodrigo Jiménez de Rada it came instead from Almeria, conquered by the Genoese in 114715. This is the Sacred Basin, now preserved at the Cathedral Museum of the Treasury in Genoa.

The artifact has the shape of very flattened hexagonal cup. So that it could resemble a stone, like the lapsit exillis. More importantly, for centuries it was really believed to be the original Grail, a hypothesis suggested by Jacobus de Varagine in the Chronicle of the City of Genoa16, not without transcending into myth. Today we know that this is not the case. The Sacred Basin was taken by Napoleon’s troops in Genoa in 1805, hence it was taken to Paris. When it was returned to the city in 1816, unfortunately broken into several fragments, it was discovered to be composed of glass paste. The hypothesis now considered most plausible is that it is a 10th-12th century artifact, made by craftsmen from the Fatimid area17.

The Holy Chalice of Valencia

Another potential Grail, which certainly has greater claims to authenticity, is the so-called chalice of Valencia. The Spanish city’s cathedral houses a precious artifact in a dedicated chapel. It is a polished cup of red agate, made in an Egyptian or Palestinian context probably between the second century B.C. and the first century A.D.18, with later additions. These include an inverted flat base made of chalcedony, the work of 10th-11th century Arab artisans; a hexagonal gold shaft, with knot and side handles, added in the Middle Ages, as well as the rubies, emeralds and pearls that adorn it.

The Chalice of Saint Lawrence

According to tradition, the chalice of Valencia was brought to Rome by Saint Peter; during the persecutions of Valerian then, exactly in 258, Pope Sixtus II entrusted it to Saint Lawrence to preserve it from destruction20. Certainly, the legend interprets hagiographic sources about the saint’s life, including Ambrose’s well-known De officiis ministrorum, which actually attests to the date and place of his martyrdom21. What concerns the Grail, however, is just a tale. Saint Lawrence is said to have sent the chalice to Huesca, his hometown, before his martyrdom.

Legend states that the artifact was then stored in the Pyrenees from 713 at the behest of Bishop Acisclus, when Muslims were taking possession of the Iberian Peninsula, and again brought back to Huesca. A document attests to its presence at the monastery of San Joan de la Peña in the 11th-12th centuries22. In 1399, the Holy Chalice appears among the possessions of King Martin I of Aragon, as evidenced by a deed from the royal palace of Barcelona23. Finally, it was Alfonso the Magnanimous24 who brought the relic to Valencia, preserved in the Cathedral since 1437.

According to another branch of the same legend, the artifact returned to Rome some time after Saint Lawrence’s martyrdom. For Alfredo Barbagallo, the Grail was hidden in the Catacombs of Ciriaca, located under the Basilica of San Lorenzo al Verano, that is, on the site of the Saint’s burial25.

The Holy Grail in Britain

Corresponding to a Medieval topos is the tradition that Joseph of Arimathea was the first to evangelize Britain, bringing with him the Holy Grail. It originated from a narrative device devised by the monks of Glastonbury to confer prestige to the local abbey. Thus, the events of Joseph of Arimathea in Brittany spread no earlier than the 12th-13th centuries, through some interpolations of William of Malmesbury’s De Antiquitate Glastonie Ecclesie (1129-1139)26, and in a similarly mythical manner the figure of Arthur was instrumentalized.

In 1184 Glastonbury Abbey suffered a severe fire, and from the ensuing economic crisis the monks recovered thanks to an – allegedly – providential event: the discovery of the tomb of the sovereign and his wife Guinevere at the monastery ensured a huge flow of pilgrims, suggesting that the famous Avalon of literature27 was hidden here. Why not exploit the popularity, in fact, of what had been narrated since the earliest sources of the 6th century, such as Gildas the Wise’s De excidio et conquestu Britannniae? By the 12th century Arthur belonged firmly in the British epos. His exploits had been celebrated in Nennius’ Historia Brittonum (9th century), in the Annales Cambriae (10th century). Finally in the well-known Historia Regum Britanniae of Geoffrey of Monmouth (1135-1137) too.

This body of narrative will finally find its completion in the work of Robert de Boron. The Grail is the divine element that leads the story of Brittany from Joseph of Arimathea to King Arthur.

Did Joseph of Arimathea really possess the Grail?

Again, the story of Joseph of Arimathea in Britain is so entrenched in the imagination that even Caesar Baronius reports a portion of it in the Annales Ecclesiastici. This is a work on church history, composed at the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries. Baronius provides precise temporal and geographical references. He states that Joseph, on his way to England where he intended to preach the Gospel, stopped in Marseilles in 35 A.D.

It should be pointed out that no source, except de Boron, much less the biblical one, explicitly reports that the Holy Grail was delivered to Joseph of Arimathea. The canonical Gospels merely state that the man received the body of Christ:

It was Preparation Day (that is, the day before the Sabbath). So as evening approached, Joseph of Arimathea, a prominent member of the Council, who was himself waiting for the kingdom of God, went boldly to Pilate and asked for Jesus’ body

Gospel of Mark 15, 42-43

Therefore, even if Joseph of Arimathea really lived in Britain, as the hagiographic myth claims, it is not certain that the historical Grail ever reached there.

The places of the Grail

On the same basis, through the pilgrim figure of Joseph of Arimathea or the ever-present Templars, the historical search for the Grail has taken on a local dimension over time: there are many places that claim, of course, its only hiding place. The holy chalice, in fact, can never be found, and therefore every town, city or region is its plausible custodian.

In Aquileia

Thus, we find it buried somewhere in Aquileia, along with the untraceable treasure of the Patriarchate. It is said that upon the arrival of Alaric’s hordes in 40128, the vast riches of the local church were hidden and never found again. Among them would be the Grail, brought there by Joseph of Arimathea, on his way to escape the persecution of the proto-Christians in the Holy Land.

In the attic of a private home in Rugby, England

Englishman Graham Phillips claims to have found the Holy Grail inside an attic in Rugby, based on the reconstruction of family trees29. The attic owner Victoria Palmer, according to the study’s author, is descended from a family of Welsh kings, the Powys, who allegedly received the Grail as a gift in the 1100s. This would have been found inside the tomb of Jesus by Helena, the mother of Emperor Constantine.

At Castel del Monte

Another possible hiding place of the Grail is Castel del Monte in Andria. The building was commissioned by Frederick II of Swabia, who supposedly came into possession of the grail during the period of Christian rule in Jerusalem. Frederick II would have hidden the Grail inside Castel del Monte, whose octagonal shape resembles a chalice.

At the Basilica of Collemaggio in L’Aquila

So many things are told about Celestine V: it is known that he was a very poor hermit, but that he managed to have an imposing basilica built near Collemaggio in L’Aquila; that he later became pope for a very short period, from April 1292 to December 1294, when he decided to renounce the papal throne to regain his lost tranquillity; and other mysterious rumours, such as his relations with the Templar order30. It is possible that Celestine met Grand Master Guillaime de Beaujeu during Council II in Lyon. There he had gone to ask Pope Gregory X for approval of his congregation. Legend says that the Knights Templar financed the construction of Collemaggio in exchange for the safekeeping, in that basilica, of an extraordinary relic from Jerusalem…

In the Hermitage of Montesiepi in Tuscany

The Inquisitio in partibus, containing the acts of the canonisation process of 118531, narrates the life of Galgano Guidotti, a knight of noble origins born in Chiusdino between 1148 and 1150. Galgano converted following a mystical vision. Then, with a resolute gesture, plunged his sword into a stone. This is the relic still today at the Hermitage of Montesiepi in Chiusdino.

And having drawn his sword, not being able to make a cross from the wood, he immediately planted the same sword in the ground as a cross. And it, by divine virtue, was welded together in such a way that neither he nor anyone else, by any effort whatsoever, was ever able to pull it out.

Inquisitio in partibus, 1185

There are some similarities between hagiography and the theme of Brittany. First of all the evocative gesture of Galgano, Arthur reversed, who instead of pulling his sword from the rock, plunges it into it. Hence the idea that the Holy Grail is in Chiusdino, where the presence of the Knights Templar is also attested.

In the Basilica of Saint Nicholas in Bari

On 9 May 1087, the remains of Saint Nicholas, Bishop of Myra, arrived in Bari, transported by sailors. The Saint’s relics had been brought through a secret mission to Asia Minor by the will of Gregory VII. The Pope ordered the construction of the city’s famous basilica in the following years. According to a popular tradition, the sailors from Bari also found a precious chalice in Myra. It was the Holy Grail.

It would be kept in the Basilica of Saint Nicholas, as suggested by a number of clues: a reproduction of the Spear of Longinus; the sculptural elements of the Lion’s Gate, where the Knights of King Arthur’s Round Table are depicted; a mysterious Latin inscription engraved on an altar in the right transept, which no one has yet managed to decipher. An interpretation of the latter was provided by Vincenzo dell’Aere32 in relation to the presence of the Grail: “The chest and casket from the crypt of Mira and the chalice from the sacellum of the Eternal of Galgano are hidden here” [Arca testa tecta a cripta in Mira et gradale a sacel(lo) in Galva(ni) sepulcr(o)]. It is worth mentioning that there is an analogy between the figure of Saint Nicholas, bestower of gifts and care, and the Grail in Medieval literature.

The Holy Grail and the Knights Templar

Another strand of research, somewhere between reality and myth, states that the Templars found the Grail in Jerusalem. Then, they transported to France. However, when the Order was dissolved (1312-1314), it was placed in a safe place. The aim was to prevent it from falling into the hands of Philip the Fair. Furthermore, it is likely that a large group of Templars managed to escape across the Channel during the persecutions of the king of France, as granted by Clement V in the aftermath of the process of Chinon33. According to some scholars, the Holy Grail was therefore transported to Scotland, inside William Sinclair’s Rosslyn Chapel34, famous for its two columns known as “of the master” and “of the apprentice”.

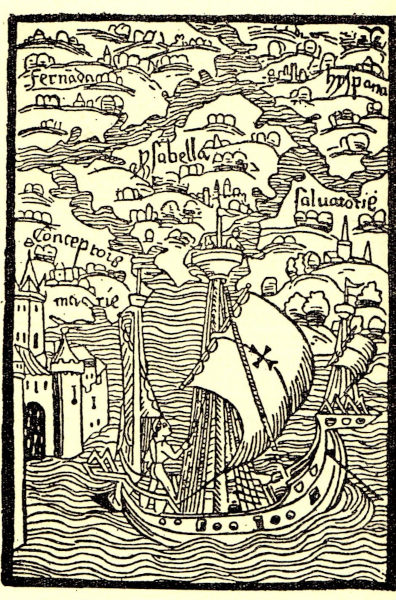

Another legend linked to the Knights Templar states that the chalice is located inside an impenetrable well (‘money pit’) on the island of Oak, Nova Scotia35. Prince Henry Sinclair is said to have commissioned a fleet from the Templars survived the persecution of Philip the Fair. They, under the command of Antonio Zeno, would have reached America… a century before Christopher Columbus. This would explain why the Cross Pattée was on the sails of the caravels Niña, Pinta and Santa Maria, as indicated by an illustrative woodcut from 1493 accompanying the Genoese navigator’s letter De insulis in mari Indico nuper inventis.

Some modern interpretations of the Grail

Parallel to historical research, a different interpretative critique of the real meaning of the Holy Grail has developed over time. According to some authors, it does not necessarily correspond to a material object. It could be rather a metaphor, a mysterious signifier underlying an idea or esoteric knowledge.

We can trace the genesis of the modern, esoteric myth of the Grail in the work of Richard Wagner (1813-1883), and in particular in his Parsifal (1882). The musician had the merit of bringing back into vogue those chivalric novels that had only been popular in the Middle Ages for half a century, from Chrétien de Troyes’ Perceval (1175-1190) to the last novels of Queste (1230), and that had only been reworked by Thomas Malory in the 15th century. At the same time, Wagner charged the tales with a modern fascination, skilfully mixing different symbolism, sensibilities and spirituality, a factor that enabled him to enjoy enormous success. From then on, the Grail myth took on new attributes. To use a profound expression from Wagner’s Parsifal, the place of its safekeeping was sought where “space becomes time”.

The Holy Grail and the Cathars

The link between the Grail and the doctrine of the Cathars was proposed in 20th-century occultist circles, especially by Otto Rahn in his Crusade against the Grail36. The Cathars, also called Albigensians in France, did not believe in resurrection. Their teaching was based on a dualism that recognized God as the lord of spiritual things and Lucifer as the creator of the material world. The Church accused them of heresy and excommunicated them, as they claimed to be unrepentant. Nor were Saint Bernard of Clairvaux’s attempts to evangelize them in Languedoc worthwhile. When the papal legate Pierre de Castelnau was assassinated in 1208, Pope Innocent III proclaimed a crusade against them. The persecution of the Cathars went on for decades until, in 1244, the Albigensian stronghold at Montségur in Occitania capitulated.

In occultist literature, the Grail is still a physical object, but associated with a secret and heretical doctrine. It could be revealed only to the purest Cathar adepts at the last degree of initiation. Otto Rahn, who moreover takes up a theme already proposed by Antonin Gadal, points out the linguistic correspondence between the name of the castle of Munsalvaesche, where Wolfram von Eschenbach places the Grail in Parzifal, and the stronghold of Montségur. Well, the sacred chalice would have been hidden in a safe place after the destruction of the fortress. Otto Rahn’s writings finally reached the hands of Heinrich Himmler, Reichsführer of the notorious German SS. In the belief that the Grail could be found, the Nazis commissioned Rahn himself to search for the chalice but, one would say fortunately, in vain.

Christ’s descendants

Also for M. Baigent, R. Leigh and H. Lincoln37 the Cathars supposedly possessed the Grail. However, for these authors, it was not an object but a most precious secret to be guarded at all costs. During the fall of Montségur, they recount, someone transferred it to a nearby location, known as Rennes-le-Château. The place was at that time an important Albigensian stronghold. So we come to 1885, when the priest of the small village church, named after Mary Magdalene, suddenly became rich. No one knows how Bérenger Saunière obtained this money. Yet there is tangible evidence of this. The parish priest spends millions to renovate the church and build a tower called magdala.

According to M. Baigent, R. Leigh and H. Lincoln, Saunière discovered the hiding place of the Grail. Not only that, he found the documents that revealed its secret: Christ had not remained unmarried, as narrated in the gospels, but had married Mary Magdalene. His descendants, over the centuries, became the Merovingian dynasty. The Grail would thus actually be the Sang Real, an image of the womb that had housed the divine seed.

This narrative made headlines and Dan Brown’s best seller The Da Vinci Code was based on it. But historians have revealed its unfoundedness. The authors based the study on a documentation by writer Gérard de Sède38. However, it was later discovered that those cipher scrolls, which contained the secret of the Grail and which Saunière allegedly found in Rennes-le-Château, were a forgery. French esotericist Pierre Plantard, in cahoots with Gérard de Sède, had invented them out of whole cloth.

The Holy Grail according to René Guénon and Henry Corbin

The thought of two 20th century philosophers who examined the esoteric aspects of the Grail, namely René Guénon and Henry Corbin, are given here in broad outline, because of the complexity of the subject matter.

René Guénon

According to René Guénon (1886-1951) the chalice was made from an emerald that fell from Lucifer’s forehead, and then given to Adam in Eden39. But the first man, through the fulfillment of sin, irretrievably lost it. What, then, is the grail? For Guénon, who compares it to the urn, a pearl representing the third eye of the Hindu deity Shiva. It would be the “sense of eternity.” The moment they ate the forbidden fruit, Adam and Eve became subject to time. They lost the unitary dimension of eternity as they drew from the tree of knowledge of good and evil, which is inherently divisive. Then, the quest for the Grail is for man the desire to return to the eternal condition of origins. And because it belongs to God, to his center, and thus to the heart, Guénon asserts that:

“the Holy Grail is the cup which contains the precious blood of Christ and which even holds it twice, having been used first at the Last Supper and then when Joseph of Arimathea collected in it the blood and water which flowed from the wound opened in the Redeemer’s side, the wound made by the centurion’s lance. In a way, therefore, this cup stands for the Heart of Christ as receptacle of his blood; it takes its place, so to speak, and becomes its symbolic equivalent;”

René Guénon, The King of the World, in M. Lings, Fundamental Symbols: The Universal Language of Sacred Science, 1995

Henry Corbin and the Imago Templi

Henry Corbin (1903-1978) takes a different path: he wants to derive the nature of the Grail from the sacred building, the Temple, that houses it40. Corbin deduces Templar notions from Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parzifal and its continuation by Albrecht von Scharfenberg, the Titurel41:

“And it is only in Albrecht von Scharfenberg’s “New Titurel”, between 1260 and 1270, that the Imago Templi rises in all its architectural magnificence. In it, the cycle of the Grail is developed into an epic of the Temple, whose climax is attained between the Temple of Solomon on Mount Moriah and the heavenly Jerusalem”.

Henry Corbin, Temple and Contemplation, 1981

Solomon’s Temple housed the manifestation of the divine presence, the shekhinah, and so was the Grail Temple. And because God wants to dwell in the heart of man, temple architecture is an imago. It is an idealized symbol of what everyone should be:

“As the Temple is constructed of the most noble materials, so should man be, since God desires to dwell in the human soul”.

Henry Corbin, Temple and Contemplation, 1981

As an archetype of the perfection to which humanity must strive, the Grail Temple is thus for Corbin an eschatological prefiguration of the world.

The Grail and the Holy Shroud

Complex to prove among recent interpretations of the Holy Grail is the one proposed by Daniel Scavone. The historian argues for the thesis that the chalice is actually the Holy Shroud42: the myth of a relic containing the blood of Christ allegedly originated from incomplete reports from the East. Schiavone suggests that the Grail legend in Brittany originated from a mistranscription of the name of the royal palace in Edessa, Britio, that housed the Shroud. But to reach such a conclusion one should first have to prove that the Shroud is authentic, that it therefore existed before the work of Chrétien de Troyes, that it was kept in Edessa and known to historiography as the Mandylion… The Turin relic debate is far from its conclusion.

The Grail and the Philosopher’s Stone

There are many similarities between the Holy Grail and the philosopher’s stone of alchemical research43. Even for the lapis philosophorum is said to have the power to bestow immortality and infinite knowledge, and also to convert any metal into gold. Gold is incorruptible: the alchemist who discovers how to transmute vile matter can therefore overcome his own mortal condition. It was believed that all elements were derived from a single original substance, the ether, present in different proportions. The philosopher’s stone, purest in its composition, would have the power to catalyze the transformation of matter into ether – solve et coagula – and thus into nobler compounds such as gold.

As mentioned, it was not a kind of chemical procedure. Rather, alchemy possessed an initiatory value. It was supposed to enable one to reach a state of enlightenment, to elevate man beyond his ordinary condition. Von Eschenbach in the Parzifal describes the Holy Grail not surprisingly as a stone. Its quest might not be related to a material object. It correspond to a path of spiritual elevation, on a par with the philosopher’s stone.

The inner quest for the Grail

The word possesses an inherent power. As an expression of the logos it reveals the nature of things, which would otherwise remain unknown. From the literary beginnings of the Grail there is a dichotomy between revelation, the good, and the unspoken, the evil. Perceval’s silence before the Fisher King is not only a personal choice. It denotes a lack of existential compassion toward self and neighbor. The hero does not give proper weight to what passes before his eyes. Nor does he care why the king was wounded. Perceval decides to remain in the dark about reality. In the Christian view of the Middle Ages this is the case since he is without Divine Grace. Only the Grace can open the consciousness and guides the motions of the soul. This is the absence of the light that illuminates the darkness; it is the rejection of ontological knowledge.

All of the literature is consequently focused on a quest that is not about possession of an object. Indeed it changes from novel to novel and is never clear what it is. The search must discover man’s inner Grail. It is a signifier in the widest possible sense. It alludes to the desire for that elusive fullness of self, knowledge of the world and the mysteries of God, which Perceval initially lacks. The quest presupposes a journey, an even radical change of self, the attainment of an existential and better elsewhere: the aspiration for the status of a heavenly knight, the healing of the Fisher King, the rediscovery of the mythical ancestry of the Kingdom of Brittany. Finding the Grail means transcending human condition and attaining the attributes of the divine. However, only the pure in heart can approach God, only the pure in heart are worthy of immortality.

Samuele Corrente Naso

Notes

- É. Gilson, La mystique de la gràce dans la Queste del Saint Graal, in Les Idées et les lettres, Paris, Vrin, 1955. ↩︎

- Chrétien de Troyes, Le Roman de Perceval ou le conte du Graal, around 1175-1190. ↩︎

- F. Cardini, M. Introvigne, M. Montesano, Il Santo Graal, Giunti editore, 2006. See also: Elinando di Froidmont, Chronicon, around 1123, where the term gradalis indicates the Last Supper dish, in G. Sessa, Graal simbolo millenario: Leggenda, Storia, Arte, Esoterismo, Ed. Arkeios, Roma, 2019. ↩︎

- Chrétien de Troyes, The story of the Grail, translation by Burton Raffel, Yale University Press, 1999. ↩︎

- A. Nutt, Studies on the Legend of the Holy Grail, With Especial Reference to the Hypothesis of its Celtic Origin, David Nutt, London 1888; W. A. Nitze, The bleeding lance and Philip of Flanders, The Mediaeval academy of America, 1946. ↩︎

- Legend Baile in Scàil, 11th century in J. Pokorny, Zeitschrift fur Celtische Philologie, XII, 1918. ↩︎

- J. Marx, La Légende Arthurienne et le Graal, Slatkine, Geneve, 1996. ↩︎

- Irish legeng of the Thuata Dé Dannan, 9th century. ↩︎

- F. Zambon, Il libro del Graal, Ed. Adelphi, 2005. ↩︎

- Wolfram von Eschenbach, Parzival, translation by E. H. Zeydel, Edwin H., and B. Q. Morgan, The Parzival of Wolfram von Eschenbach: Translated into En-glish Verse with Introduction, Notes, Connecting Summaries, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1951. ↩︎

- R. Barber, Graal, Piemme, Casale Monferrato, 2004. ↩︎

- Robert de Boron, “Roman dou l’Estoire de Graal ou Joseph d’Arimathie”, 13th century. Ms. E.39, Biblioteca Estense di Modena; ms. nouv. Acq. Fr. 4166, Biblioteca nazionale di Parigi. ↩︎

- Ibidem note 11. ↩︎

- William of Tyre, Historia in partibus transmarinis gestarum, 1184. ↩︎

- Rodrigo Jiménez de Rada, Historia de rebus Hispanie sive Historia Gotica, beginning of the 13th century. ↩︎

- Jacobus de Voragine, Cronaca di Genova dalle origini al MCCXCVII, Tipografia del Senato, 1941. ↩︎

- Restoration conducted by the Opificio delle Pietre Dure in Florence, whose study is published at this link. ↩︎

- A.Beltrán, Estudio sobre el Santo Cáliz de la Catedral de Valencia, Valence, 1960. ↩︎

- By Jl FilpoC – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, image. ↩︎

- Thomas J. Craughwell, Saints Preserved, Crown Publishing Group, 2011. ↩︎

- Ambrose of Milan, De officiis ministrorum, about 390. ↩︎

- D. Carreras Ramirez, Canon of Zaragoza, Vida di S. Laurenzo,14 dicembre 1134: “En un arca de marfil está el Cáliz en que Cristo N. Señor consagró su sangre, el cual envió S. Lorenzo a su patria, Huesca;”. ↩︎

- Pergamena 136, archives of the Crown of Aragon, Colecc. Martin el Humano, Barcellona. ↩︎

- Deed of notary Jaume Monfort, dated March 18, 1437. ↩︎

- A. M. Barbagallo, San Lorenzo e il Santo Graal. Ipotesi di studio interpretativo su presenze storico artistiche, archeologiche ed iconografiche nell’area basilicale di San Lorenzo fuori le Mura in Roma, 2007-2009. ↩︎

- J. A. Robinson, William of Malmesbury ‘On the Antiquity of Glastonbury’ in Somerset Historical Essays, Oxford University Press, London, 1921; John Scott, The Early History of Glastonbury: An Edition, Translation, and Study of William of Malmesbury’s De Antiquitate Glastonie Ecclesiae, Boydell Press, 1981. ↩︎

- Giraldus Cambrensis, De principis instructione, 1193. ↩︎

- Zosimus, Historia Nova, V, 37.2. ↩︎

- G. Phillips, La ricerca del Santo Graal, Sperling & Kupfer Editori, Milano, 1996. ↩︎

- M. G. Lopardi, Celestino V e il tesoro dei Templari, 2010. ↩︎

- Inquisitio in partibus, from the canonisation process (1185) as transcribed by Sigismund Tizio in Historiae Senenses, Cod. Chigi G. I. 31; F. Scneider – Analecta toscana, IV, Der Einsiedler Galgan von Chiusdino und die Anfaenge von S. Galgano – in Quelle und Forschungen aus Italienischen Archiven und Bibliotheken, XVII, 1914-1924. ↩︎

- ↩︎

- B. Frale, Il Papato e il processo ai Templari. L’inedita assoluzione di Chinon alla luce della diplomatica pontificia, Viella, 2003. ↩︎

- T. Wallace-Murphy; M. Hopkins, Rosslyn: Guardian of Secrets of the Holy Grail, 1999. ↩︎

- S. Sora, The Lost Treasure of the Knights Templar, Inner Traditions/Destiny, 1999. ↩︎

- O. Rahn, Kreuzzug gegen den Gral. Die Geschichte der Albigenser, Broschiert, 1933. ↩︎

- M. Baigent, R. Leigh e H. Lincoln, Il Santo Graal – Una catena di misteri lunga duemila anni, Mondadori, 2003. ↩︎

- G. de Sède, “Le trèsor maudit”, 1967. ↩︎

- R. Guénon, The King of the World, 1927. ↩︎

- Henry Corbin, Temple and Contemplation, 1981. ↩︎

- A. von Scharfenberg, Der Junge Titurel, 1268-1275. ↩︎

- D. Scavone, Joseph of Arimathea, the Holy Grail and the Turin Shroud, 1996. ↩︎

- A. Cerinotti, Il Graal, Giunti editore, 1998. ↩︎