In Sardinia, an ancient spiritual feeling that aims at self-knowledge and understanding of the world is expressed through stone since the Palaeolithic age. Stone is thus moulded as an image of one’s own being, anthropomorphic features become increasingly explicit in art, and architecture is the full expression of the sacredness. The ancient Sardinians trace thresholds among distant worlds. They seek the essence of the reality in the imaginary, create rituals with archaic powers. The slow affirmation of pre-Nuragic cultures is known to us through the fruits of this process. It involves both the material aspects of everyday life and the dimension of the transcendent. Rites of passage characterized the hierophanies of that time, albeit in changing forms, and the funerary architecture. So, the Sardinian hypogeic tombs, collective burials known as domus de janas, developed simultaneously with the megalithic dolmen tombs.

The Sardinian hypogeic tombs: the domus de janas

The name domus de janas, evocative in its references to fairy houses, is a result of popular culture. Overtime, people forgot the original use of those rooms carved out of stone. In Sardinia, there are more than three and a half thousand domus de janas. They belong, in most cases, to the Ozieri anthropological context, which constituted a cultural avant-garde of its time. However, the use of hypogeic tombs could date back to even earlier times, perhaps to the Middle Neolithic, in correspondence with the San Ciriaco culture, a late aspect of the Bonu Ighinu facies1.

The sacred architecture of the domus de janas

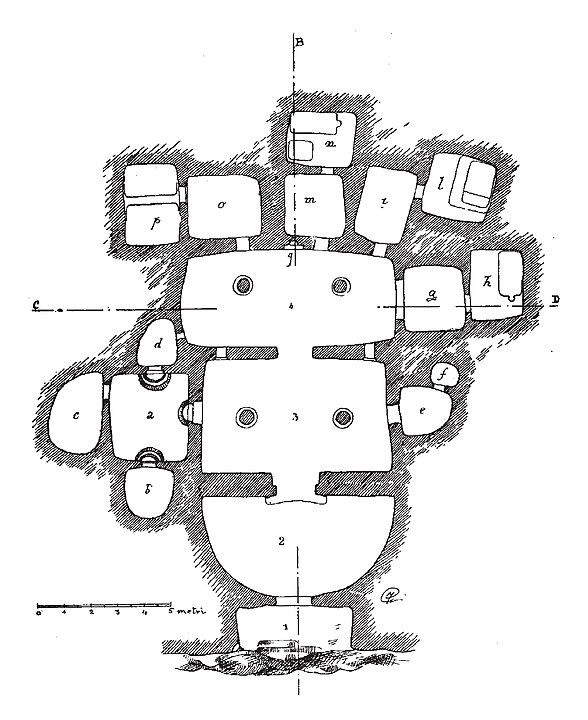

The domus de janas are carved into the rock. They consist of at least two rooms, comprising an antechamber, a small entrance room used for transporting the deceased, and a burial chamber. The addition of further cells could enlarge this basic form. A monumental entrances or dromos introduces to the domus de janas. However, the entrance could also be more hidden, pit type, below the ground level.

A difference in ritual purposes is evident between these two types of entrance. In the case of the pit tombs, a desire for privacy prevails, perhaps even a concern to confine the deceased to the tomb for fear that he could, frighteningly, return from the afterlife2. The monumental entrances, provided with a larger antechamber, suggest instead collective ceremonies for the entire community, apotropaic rites of passage endowed with the necessary efficacy to ward off the return of the undead. In this case the presence of a dromos corridor served to welcome the ritual procession that carried the deceased into the womb of Mother Earth.

The ancient Sardinians believed, in fact, that life continued beyond death, that man was reborn in a new dimension, no longer from a mother’s uterus, but from the womb of the earth itself4. The rite of burial accompanied this ideal transit. So, the architecture of the domus de janas was an intrinsic and fundamental component of it. They represented the symbolic, metaphysical space of the passage to the afterlife.

The Sardinian hypogeic tombs and the rite of passage to the afterlife

The rite of passage consisted of a preparatory phase in which the deceased was first semi-burnt5. He was then led into the antechamber through a narrow opening, the portello. It recalled the dimensions of the mother’s womb, a symbolic assumption for rebirth. Finally, inhumation took place in the sepulchral chamber. The dead was buried in the foetal position and covered in red ochre. The blood colouring, remembering the birth of a newborn, evoked the event of a new life in the afterlife. The metaphysical boundary, the ideal threshold of the transit, is realised by the architecture of a false door, located near the bottom chamber of the domus de janas. This leads to another dimension, numinous, since it cannot be passed through by the living.

The imaginary architecture of the false door is the chosen place where the effectiveness of symbols is manifested. On the lintel, the stylisation of the head or the horns of an ox carved, engraved or painted sometimes recurs. The ox, on the other hand, was of fundamental importance in the agricultural economy of Neolithic societies. This animal, used to pull the plough, ensured the fertility of the soil and the seasonal awakening of life. Figuratively, it fertilised Mother Earth. Likewise, the deified bull was believed to have the power to evoke the rebirth of the deceased into a new, supersensible world. Crossing a door, false or real, crowned with the bovine protomes, meant entering the animal’s head and symbolically assume its nature7, having the same power to regenerate life.

The “Goddess of the Eyes” of the Sardinian hypogeic tombs

While the male generating principle was expressed through the bucranium or bovine protomes, the female archetype was embodied in the nature of the Earth itself. She, as mother, welcomed the dead as children in the womb. Spirals and concentric circles, signifying the cycles of life regeneration, are sometimes present in the antechamber or main chamber. When such spirals or circles are arranged in pairs, they are anthropomorphic attributes of the Mother Goddess, who is then called “Goddess of the Eyes”8.

It is as if the Mother Earth were watching over the successful transit of its children. Similarly, the numerous cup marks found on the floor of the domus de janas are a manifestation of the female presence of the Goddess. The cup marks, similar to inverted breasts, probably had a cultic function, now forgotten. It is plausible that they served to contain libations, votive offerings or animal sacrifices.

The continuity of life in the afterlife

The idea of an ordinary continuation of existence in the afterlife required that burial chambers mimic the architecture of the living, at least in its essential elements. In the Sardinian hypogeic tombs of the domus de janas we find representations of pitched roofs, pillars, lesenes, doors, fireplaces, even the entire floor plan of pre-Nuragic dwellings. At the Tomb of the Chief in the necropolis of Sant’Andrea Priu, in Bonorva, the sculpted ceiling of the semicircular vestibule reproduced the roof of a hut and its beams. It is interesting to see how this custom allows us to learn about certain aspects of otherwise obscure pre-Nuragic civilisations. For the same reason, during the burial ritual, ancient Sardinians placed tools and jewellery typical of life inside the chamber. We could find arrowheads, shells, necklaces, bracelets and various types of pottery.

A different function had the working tools used to dig the graves, usually stone spikes. These were objects with an intrinsic sacred value, used to shape the womb of Mother Earth. The spikes were made within the domus de janas and then added to the grave goods of the deceased10.

Millennial use of the domus de janas, the Sardinian hypogeic tombs

The use of domus de janas, sometimes for more than two thousand consecutive years, is attested until the Early Bronze Age. This is a period the growing trend towards megalithism influenced the hypogeic burials. In several domus de janas the entrance gallery is now completely dolmenic or allée couverte. Instead, in others the door imitates and anticipates the frontal exedra of the tombs of the giants.

However, the sacred ambience that characterises the domus de janas survived beyond the pre-Nuragic cultures and even the Nuragic period. In some cases, a late reuse with a change of function is visible. At the Tomb of the Chief, dating back to the end of the Neolithic (3000 B.C.) and belonging to the Ozieri culture, in the Byzantine period we have a radical readaptation of the rooms. In this period they had no longer funerary purposes but used as a church. The walls of the cells, frescoed with scenes from the gospels and Christian symbols, created an exceptional mixture of figurative elements thousands of years apart.

The megalithic architectures

Simultaneously with the spread of the domus de janas, burials carved directly into the womb of the Mother Goddess, epigeic architecture developed in Sardinia. The first complete manifestation of a funerary structure emerging from the ground is visible in some circle tombs near Li Muri, in Gallura.

The tombs of Li Muri are dated by some scholars to the Recent Neolithic (3400-3200 BC) and therefore attributed to the Arzachena culture11, by others to the Middle Neolithic12. The deceased rested there inside lithic cists. They consisted of four small stone blocks set along a quadrangular perimeter. However, we do not know if a top slab covered them. Each cist, of which there were originally five at Li Muri, is surrounded by concentric circles of slabs set into the ground, up to eight and a half metres in diameter. They probably served as a support for mounds of stone and soil. Both outside and inside the circles were small menhirs.

The dolmens of Sardinia

The lithic cist circles of Li Muri are not properly megalithic. They lack the monumentality of the stone blocks used, an element that characterises dolmens from the Recent Neolithic onwards. It is only with the Ozieri culture (4100 – 3500 B.C.) that funerary architecture of the gigantic order spread throughout Sardinia. This term is used from then on in the definition of Nuragic burials. The dolmens of the pre-Nuragic period, approximately two hundred and forty in number, located mainly in the central-northern part of the island13, are characterised by the juxtaposition of stone slabs, called orthostats, in such a way as to form a covered burial chamber for the inhumation of the dead.

Sardinian dolmens differ in their construction types according to the burial chamber orientation and the presence of an entrance corridor. This may be allée couverte or dromos, with or without roofing slabs. Most megaliths, however, are of simple construction, without a corridor, as at the archaeological site of Sa Covaccada in Mores.

The dolmen of Sa Covaccada is one of the most important megalithic monuments in Sardinia. Its dimensions are imposing. The megalith is more than two metres high, and certain functional and symbolic elements are of exceptional character. One of the side orthostats houses a niche, already planned in the design phase. Furthermore, a frontal slab with a small door covers the entrance to the burial chamber. This choice anticipates the exedra-shaped architecture of the Nuragic tombs of the giants.

The cultic aspects

Some dolmens in Sardinia stand inside a circle of boulders, called peristalith. Nonetheless, it is not clear whether this had a structural function, as a residue of the covering of a mound, or a cultic one. In the latter sense it could correspond to a sacred threshold between the world of the living and that of the dead15. Also expression of rites of passage were the cup marks, engraved on altar-boulders not far from the dolmen, even carved into the surface of its orthostats or the covering slab.

Such megaliths, generally isolated, are on plateaus and valleys. This is an indication that they were the expression of people who dedicated to pastoralism. Being located in the countryside, the dolmens of Sardinia were territorial markers that still characterise the landscape today. Possibly those burial rituals associated with them involved particular members of the community, suggesting a social stratification of the pre-Nuragic peoples. This seems true even for the contemporary domus de janas, Sardinian hypogeic tombs hidden from view. However, what was the cultic or social criterion behind the choice of sacred architecture is not yet known.

Samuele Corrente Naso

Notes

- G. Tanda, L‘ipogeismo funerario in Sardegna. Nel volume: A. Moravetti, P.Melis, L. Foddai, E. Alba, La Sardegna Preistorica, Corpora delle antichità della Sardegna, 2017, Carlo Delfino editore & C. ↩︎

- P. Melis, La religiosità prenuragica. Nel volume: A. Moravetti, P.Melis, L. Foddai, E. Alba, La Sardegna Preistorica, Corpora delle antichità della Sardegna, 2017, Carlo Delfino editore & C. ↩︎

- A. Taramelli – Fortezze, recinti, fonti sacre e necropoli preromane nell’agro di Bonorva, in Monumenti Antichi dei Lincei, vol. XXXV, Roma 1919. ↩︎

- E. Contu, La Sardegna preistorica e nuragica: La Sardegna prima dei nuraghi. Chiarella, 1997. ↩︎

- M.G. Melis, La dimensione simbolica e sociale della Sardegna preistorica attraverso le manifestazioni funerarie. Alcune osservazioni, «SCBA», IX, 2011c. ↩︎

- Di Gianni Careddu – Opera propria, CC BY-SA 4.0, image. ↩︎

- G. Lilliu, La civiltà dei sardi dal Paleolítico all’età dei nuraghi, Il Maestrale, 2004. ↩︎

- Ibidem. ↩︎

- By Archeologosardos – CC BY-SA 3.0, image. ↩︎

- Ibidem note 1. ↩︎

- G. Lillliu, Aspetti e problemi dell’ipogeismo mediterraneo, Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, 1998; E. Atzeni, Aspetti e sviluppi culturali del neolitico e della prima età dei metalli in Sardegna. Nel volume: AA.VV, Ichnussa – La Sardegna dallle origini all’ età classica, Libri Scheiwiller, 1981. ↩︎

- L. Alba, Nuovo contributo per lo studio del villaggio neolitico di San Ciriaco di Terralba (OR). Nel volume: L. Alba et al., Studi sardi, Edizioni AV, 2000. ↩︎

- R. Cicilloni R., I dolmen della Sardegna, PTM Editrice, 2009. ↩︎

- Di zagordemores – Flickr, CC BY 2.0, image.

↩︎ - B. D’Arragon, Presenza di elementi cultuali sui monumenti dolmenici del Mediterraneo centrale, Rivista di scienze preistoriche vol. XLVI, issue 1, 1994. ↩︎