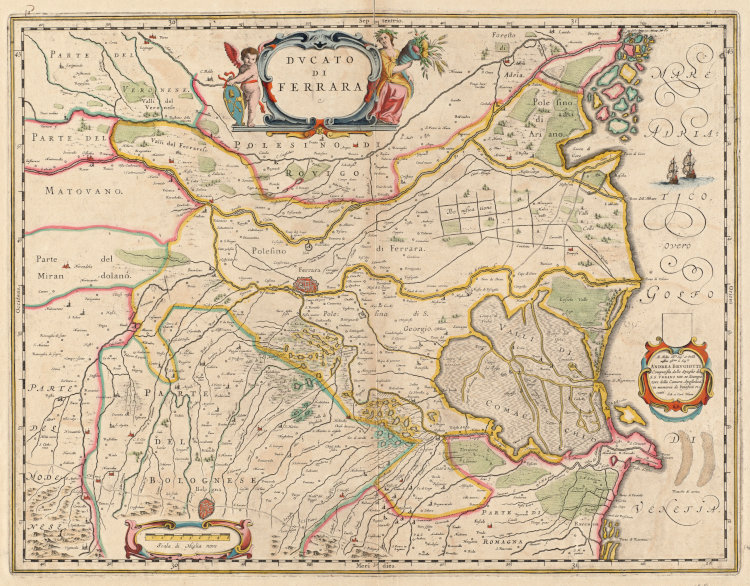

That strip of land between the branches of the Po Delta, Goro and Volano, and enclosed by the Adriatic lagoons further east, became increasingly unhealthy. The green forests that the Romans had carefully governed and the reclaimed expanses were a memory. Rather, they appeared as a valley of pristine and treacherous marshes. Historians identify the “Rotta di Ficarolo” of 1152, and the subsequent events of escaping the banks of the Po, as the beginning of a slow process of land transformation. The path of the river and its habitual march over centuries-old banks began to vary wildly1, sowing putrid marshes and malaria where life seemed unquenchable.

Even at the dawn of the second millennium, historiographical sources tell us of lush vegetation, even bursting forth in its pleasant harmony. Here, in the Po Valley of Emilia-Romagna, the Insula Pomposiana stood out flourishing. This was the name of the largest of the islands, no longer such, that the Po returned to the mainland in the midst of a jagged lagoon. Pomposa, although surrounded by water, was an important place of passage. The island was situated along the route of the ancient Roman Via Popilia. This walkway connecting it to Ravenna was named Via Romea. Through this centuries-old roadway pilgrims came to Rome from the East and the northern moors.

The coenoby of Pomposa, historical notes

Pomposa, with its forests, silence cradled by the waters and favourable geographical location, offered the best place for monks. Near the present territory of Codigoro the existence of a Benedictine abbey is attested as early as 874. In a missive, dated January 29 of that year and addressed to Emperor Ludwig II2, John VIII intervened in a judicial dispute, expressly mentioning Pomposa. The pope reiterated that the “monasterium sanctae Mariae in Comaclo quod Pomposia dicitur” was to remain a dependent territory of the Holy See. It was in opposition to the objections of the archbishop of Ravenna who claimed ownership.

Nonetheless, the first settlement of a monastic community dates much earlier: some archaeological investigations, conducted at today’s Pomposa Abbey, show the presence of remains datable to the 6th-7th centuries3. These include an altar, mosaic fragments and a chapel near the chapter house. In Lombard times, the island of Pomposa belonged to the monastic fiefdom of Bobbio, which is why the existence of a preexisting cult building dedicated to Saint Columbanus4 is conceivable. Following the upheavals that affected Italy after the descent of Charlemagne, Benedictines soon had to arrive in Pomposa. The region of the Great Po River was easily accessible from Cassino. It was a strategic location, as it allowed missionaries to make stopovers along the routes to the East.

The Benedictines and Pomposa Abbey

The Benedictines laid the foundations of what is now known as Pomposa Abbey, although considerably remodelled later, perhaps even rebuilt. In fact, historiographical sources seem rather scarce. Only with difficulty is it possible to reconstruct the events that involved the Codigoro coenoby in the centuries immediately following. Gina Fasoli claimed that the Abbey was devastated by the Hungarians during raids in Italy (899-900) and had to be refounded5.

It is possible that the reconstruction was promoted by imperial intervention: Pomposa is mentioned again in a diploma dated on the 30th October 982 through which Otto II handed it over to the dependencies of the monastery of San Salvatore in Pavia6. With Otto III, however, the coenoby was first assigned to the church of Ravenna (999). From that time on, Pomposa Abbey was subject to continuous changes of jurisdiction, oscillating between being a monastic fief of Pavia or Ravenna.

Guido’s abbey and the period of greatest splendor

It was only during Guido’s abbey that the stability was achieved, which allowed the monastery to renew itself profoundly. Then a period of very important cultural flourishing began. It was during these years that Pomposa assumed its present architectural conformation. In fact, the rededication of the church is attested to 10267. At the same time extensive renovations were to be completed, led by a certain master from Ravenna, Mazulo, which involved the atrium and partly the mosaic floor in opus sectile. During this period Guido Monaco, also known as Guido d’Arezzo, came in Pomposa. He developed here the modern system of musical notation, which later spread throughout the world8.

In 1063 the architect Deusdedit raised the tall bell tower (48 meters) that still stands unchallenged over the Po Valley. In addition to the church of Santa Maria, the abbey complex was completed in these years by the adjoining monastery and the Palazzo della Ragione, inside which the abbot exercised the temporal power conferred on him by the emperor. Also preserved here was an exceptional library collection that had reached its peak under Abbot Jerome. Unfortunately, only a few manuscripts have survived of the Pomposa library. However, enough to give an idea of its importance in the 11th and 12th centuries.

The decline of Pomposa Abbey

With the gradual change in the hydrographic setting from the 12th century onward in the Po Delta region, living conditions in Pomposa became increasingly untenable. It is possible to identify a last period of artistic flourishing when Pietro da Rimini and Vitale da Bologna painted, respectively, the masterful frescoes at the refectory (1316-1320) and the apse (1351). The coenoby of Pomposa then gradually lost importance and prestige, until the annexion to the Estensi of Ferrara’s possessions. So, the relocation of the monks to a city monastery dates back to 1553. Exactly a century later Pope Innocent X decided on its final suppression.

The church of Santa Maria

On the right side of Santa Maria in Pomposa narthex, a clay face looks sternly at visitors. Tradition says that face belongs to the builder of the atrium, who left his name in a plaque: Mazulo magister. He had to add the narthex just before 1026, the year of the Abbey rededication. Mastro Mazulo carried out his architectural intervention as an expression of beauty, as a rediscovery of the ancient. He made extensive use of reused materials, stone or fictile, belonging to pre-existing buildings, even from several centuries ago. He also merged very different cultural styles: on the facade of the atrium it is possible to find Byzantine and Islamic, Lombard and Romanesque influences.

The church of Santa Maria greets visitors from the outside with its majestic bell tower of Lombard area. Dating from 1063, as an inscription at the base attests, it is the work of the architect Deusdedit. The bell tower has got nine orders of windows. They increase in size as proceeding upward, so as to lighten the weight of the structure. Hence, the monofora on the second floor are followed by two, three and four mullioned windows upward.

The symbolism of exteriors

Three horizontal bands of carved tiles decorate along the atrium facade and the arches depicting phytoform and animal motifs. Note the presence of a monk on the lower right band and symbols from the Medieval bestiary, including the griffin. The friezes also include an image of Jonah swallowed by a whale.

The polychrome bowls of Pomposa Abbey

On the facade of the atrium are eight polychrome terracotta bowls, made with the engobe technique, of Egyptian-Coptic ancestry. Inside them can be glimpsed the symbol of Pomposa Abbey: an eight-pointed star. The bowl motif is also echoed on the bell tower, where they contain painted animals or fantasy designs.

The symbolic function of the bowls is to reflect the sun at noon. No one can observe the sun with the naked eye but only its reflection. Likewise to get to Christ is needed the intercession of Virgin Mary and Saint John the Baptist. It is no coincidence that we can find this symbolism (deesis) in the Rimini School fresco cycle at the refectory.

Among the eight bowls in the atrium are several stone tiles with strong symbolic meaning. In particular, the peacock, eagle and lion belong to the bestiary connoting Christ’s virtues.

The elements of reuse

The facade of the atrium hosts numerous reused elements. These include a marble cross possibly from an iconostasis of an older, Ravenna-influenced church (Fig.1); the bust of a Roman soldier, placed on the atrium during work carried out in the 12th century (Fig.2).

On either side of the three arches opening onto the atrium are two circular transennae, inside each of which depicts a tree of life and griffins feeding on its fruit. According to Salmi, the two transennae, probably Lombard reused material, imitate those of the lost Porta Aurea in Ravenna9. The features of the tree of life were the object of different interpretations. According to Carla di Francesco10 they are influenced by Persian styles. It is possible to glimpse an important resemblance to the Irminsul of the Saxons, the great oak holding up the sky, a cosmogonic simulacrum of divinity.

The interior of the Church of Santa Maria

The abbey church of Santa Maria has a clear Ravenna inspiration. In fact, the interior mimates the basilica plans of Sant’Apollinare in classe and Sant’Apollinare nuovo; the circular apse becomes polygonal on the outside, as in San Vitale. Santa Maria is divided into a nave and two aisles, without a transept, by means of columns with Roman and Byzantine capitals. These show finely carved ornaments of leaves and vines.

The mosaic floor

The floor mosaic of the church, in opus sectile, represents one of the most valuable testimonies of the entire complex, belonging its realization to several centuries (6th-12th centuries). The motifs of the mosaic decoration include animals of deep significance: the deer, a metaphor for Christ, contrasts with the dragon, a symbol of evil. The numerous bird figures, on the other hand, represent the faithful.

The frescoes of Pomposa Abbey

The frescoes in the abbey church, however, are from the 14th century. They denote an excellent state of preservation as a whole, although we have lost some pictorial portions along the aisles.

The fresco on the central basin is an extraordinary work by Vitale da Bologna, dated 1351. It depicts Christ in Majesty, enclosed in a mandorla or vesica piscis, with angels and saints. The Virgin Mary on the right holds a scroll, through which she intercedes to God for a procession of worshippers aspiring to heaven. Along the lower bands are the four evangelists, the doctors of the Church, and some scenes from the life of Saint Eustace. These include his conversion and martyrdom, which took place inside the body of a red-hot ox.

The frescoes in the nave, by Bolognese masters, reproduce scenes from the Old Testament (upper band), the New Testament (middle band) and the Book of Revelation (lower band). The wall paintings, like the works of contemporary Medieval masters, have both a decorative and illustrative function of the Bible, since a large proportion of the faithful were illiterate.

On the counterfaçade, on the other hand, is the pictorial representation of the Last Judgment. The scene, at times gory and impressive, is meant to show visitors how actions performed in life are subject to the final judgment: salvation and damnation will continue for eternity.

The Monastery of Pomposa Abbey

The monastery, located next to the church of Santa Maria, houses rooms of extraordinary artistic importance with paintings from the 14th century: the chapter house contains frescoes of the Giotto school; the refectory exceptional works by Pietro da Rimini executed between 1316 and 1320. Both rooms are accessible directly by crossing the complex’s quadrangular cloister. All that remains of it are the four corner pillars, which include twisted columns and phytoform reliefs.

The chapter house

A Crucifixion is located on the back wall of the chapter house. A group of angels stands around the dying Christ, mourned by the Virgin Mary at his feet. On the sides of the central scene are painted figures of the apostles Peter and Paul, flanked by Saints Guido and Benedict and images of prophets.

The refectory of Pomposa Abbey

Of great artistic interest are the frescoes in the refectory. The figure of the Blessing Christ dominates the central scene between the Virgin Mary, Saint John the Baptist, Saint Guido and Saint Benedict. Laterally we can observe some scenes from the life of Saint Guido and a precious Last Supper. Episodes related to the hagiography of the saint of Pomposa include the miracle of the transformation of water into wine before the bishop of Ravenna Gebeardo.

The Palace of Reason

Not far from the monastery stands the Palace of Reason, seat of the abbot’s temporal power. The building dates from the 11th century and opens to the outside through loggias arranged in two different orders. The lower one gives access to a narrow atrium, marked longitudinally by arcades with different reused columns and brick pillars. Some capitals, finely carved, also depict the tree of life.

Samuele Corrente Naso

Notes

- A. Bondesan, M. Bondesan, Breve storia idrografica del territorio ferrarese. ↩︎

- P. Federici, Rerum Pomposianarum historia, 1781 ↩︎

- S. Patitucci Uggeri, Castra bizantini nel delta padano, École Française de Rome, 2006. ↩︎

- Saint Columbanus: an Irish moks who evangelized Piacenza during the 6th-7th centuries. ↩︎

- Incognite della storia dell’abbazia di Pomposa fra il IX e l’XI secolo, in «Benedictina», anno XII, nn. III-IV (1959), pp. 197-214. ↩︎

- M. Salmi, L’abbazia di Pomposa, Roma, Istituto Poligrafico dello Stato, 1936; L’abbazia di Pomposa, Roma, La Libreria dello Stato, 1938. ↩︎

- Ibidem. ↩︎

- Guido Monaco, Micrologus, 1026. ↩︎

- Ibidem note 6. ↩︎

- C. Di Francesco, L’abbazia e il Museo di Pomposa, De Luca, 2000. ↩︎

- Sailko, licence CC-BY-SA. ↩︎

- Sailko, licence CC-BY-SA. ↩︎